Introduction

Rectus sheath hematoma (RSH) is a rare condition defined as the accumulation of blood within the rectus abdominis muscle sheath secondary to a rupture of epigastric vessels or the muscle fibers. Importantly, the rise of anticoagulant use has led to an increase in the incidence of RSH.

Because RSH usually presents with acute abdominal pain, it can be mistaken for other acute intra-abdominal conditions leading to diagnostic confusion and delay in treatment. Therefore, in order to facilitate early diagnosis and management of RSH, it is crucial that physicians become familiar with its clinical presentation as well as diagnosis and management.

The purpose of this paper is to provide a contemporary review of the diagnosis and management of rectus sheath hematomas.

Anatomy of the rectus sheath

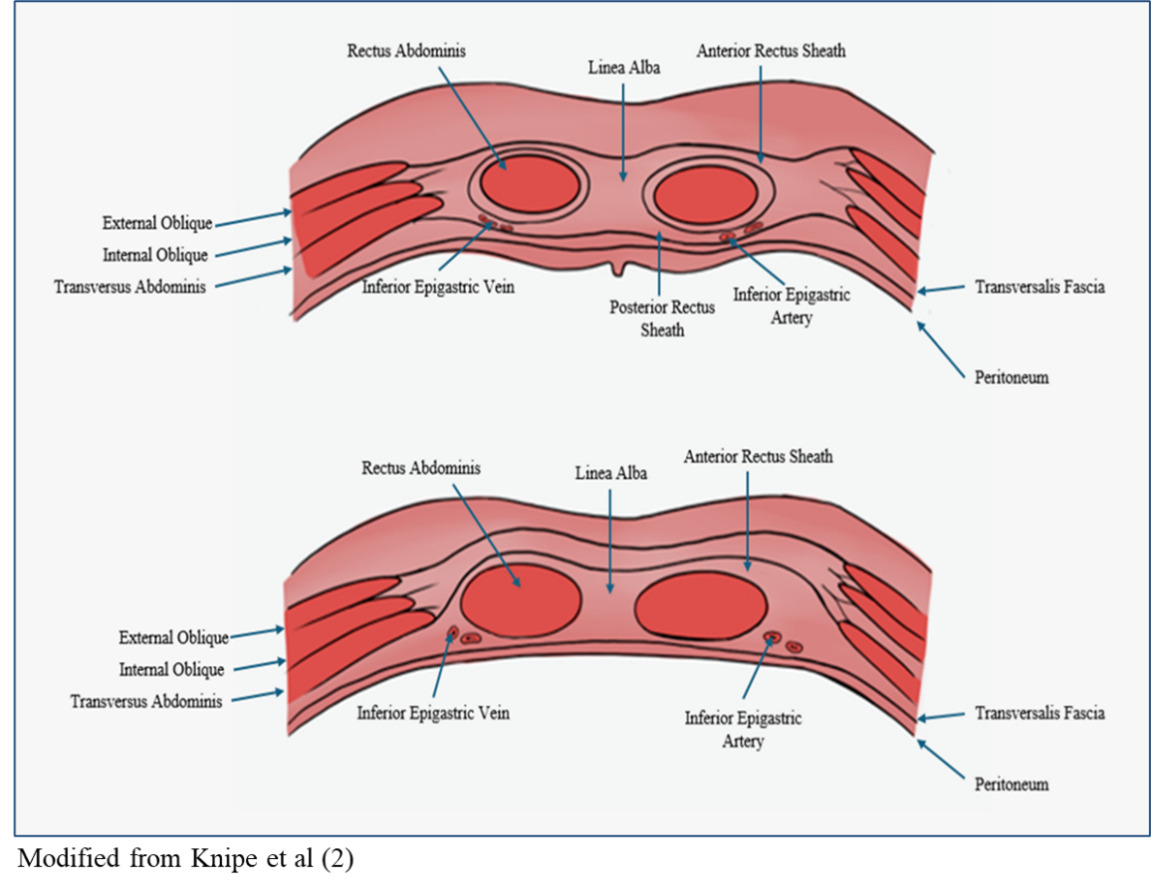

The rectus abdominis is a long flat muscle that runs along the anterior wall of the abdomen that plays a crucial role in abdominal flexion and core stability. The rectus abdominis muscle is surrounded by two layers of fascia known as the rectus sheath. This sheath of fascia is formed by the aponeuroses of the transversus abdominis, external oblique, and internal oblique muscles. These aponeuroses fuse medially at the linea alba and laterally at the linea semilunaris. The resulting structure is a posterior and anterior sheath surrounding the rectus muscle. A significant anatomical landmark in the context of RSH is the arcuate line, which denotes the end of the posterior rectus sheath supporting the rectus abdominis. It is located about 1/3 of the distance from the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis, and marks where the internal oblique aponeurosis passes anteriorly to the rectus muscle. This leaves only the transversalis fascia and peritoneum to support the posterior side of the rectus muscle.1,2

Blood is delivered to the rectus abdominis muscles via the inferior and superior epigastric arteries. The superior epigastric artery originates from the internal thoracic artery and descends along the posterior surface of the rectus abdominis. The inferior epigastric artery originates from the external iliac artery and ascends medial to the internal inguinal ring and is located superficial to the transversalis fascia (Figure 1). As the inferior epigastric artery branches upward, it crosses the lateral border of the rectus muscle at the arcuate line and enters the posterior rectus sheath. At the level of the umbilicus, the inferior and superior epigastric arteries anastomose. Without the support of the posterior rectus sheath below the arcuate line, the blood vessels become vulnerable to movement related changes.1,2

Pathophysiology

RSH is most often the consequence of dissection of either the inferior or superior epigastric arteries and subsequent bleeding into the abdominal wall. In some cases, RSH may be caused by tearing the rectus muscle itself. The inferior epigastric artery is loosely fixed to the rectus abdominis muscle below the arcuate line without the posterior fascial support of the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversalis aponeuroses (Figure 2). However, the branches of the inferior epigastric artery above the arcuate line are strongly fixed in the position where they perforate through the muscle. The combination of the loose and strong fixation of the different regions of the inferior epigastric artery makes it vulnerable to shear forces, which results in a higher likelihood of tearing.1,3 Dissection of the inferior epigastric artery adds the risk of bleeding between rectus muscle and transversalis fascia, or even into the pre-vesical space.1,4 Extension of the RSH into the retropubic space can result in increased intra-abdominal pressure and subsequent abdominal compartment syndrome.5,6 This is defined as an intra-abdominal pressure of greater than 20 mmHg with accompanying organ dysfunction.7 Dissection of the superior epigastric artery tends to result in smaller self-limiting hematomas due to the tamponade created by the bleed being contained within the rectus sheath and the muscle.

Etiology and Epidemiology

There are a variety of factors that can contribute to the formation of RSHs. One of the most common risk factors of developing RSH is the patient being on anticoagulant therapy such as warfarin, apixaban, and rivaroxaban.8 A retrospective study in 2016 by Sheth et al identified 77% of patients presenting with RSH between January 2005 and June 2009 being on an anticoagulant. Out of these patients, 46.1% were on chronic anticoagulant therapy, while 77.4% received anticoagulant therapy in the hospital. Concurrent antiplatelet therapy alongside anticoagulant therapy increases the risk of major bleeding events and bleeding related hospitalizations.9 Chronic kidney disease (CKD) in combination with anticoagulant therapy may also increase the risk of developing RSH. Decreased renal excretion from CKD can increase the exposure of the anticoagulant. CKD also affects the metabolism of anticoagulants within the liver. The downregulation of cytochrome P450 in CKD interferes with the hepatic metabolism of anticoagulants. Uremia due to CKD can also cause platelet dysfunction, thus increasing risk of bleeding events.9 There have been multiple cases of RSH formation after enoxaparin injection into the abdominal wall.10–12 Even in Sheth et al 51% of patients presenting with a RSH had received a subcutaneous abdominal wall injection.9 RSH can develop from iatrogenic causes such as the previously described abdominal wall injections, or even previous surgeries. Surgical scars may even contribute to an increased risk because they change the force distribution during muscle contraction, which makes the arteries more prone to injury.1

RSH has been seen to be more prevalent in women than in men. A retrospective study done by Cherry and Mueller displayed 64% of their RSH patients being women, which is similar to the 63.5% proportion of female patients identified in Sheth et al.3,9 This higher proportion of female patients may be due to the anatomical differences in rectus muscles combined with potential weakening of the abdominal wall during pregnancy. Advanced age has also been identified as a risk factor. The average age of patients with RSH in Chery and Mueller’s review was nearly 68 years, with the average age of patients in Sheth et al. being 65 years.3,9

Other common risk factors for development of a RSH include abdominal trauma due to either extrinsic forces or forceful contraction of the abdominal muscles. Paroxysmal episodes of coughing result in violent contractions of the abdominal muscles, which can lead to injury of the epigastric arteries.1 Direct abdominal trauma can also cause the epigastric arteries or the rectus muscle itself to tear, leading to formation of a RSH.1,13,14 In Sheth et al. one third of the patients presenting with RSH experienced a paroxysmal episode of coughing before developing the RSH.9 The repeated severe contractions of the abdominal muscles associated with paroxysmal coughing can result in injury to the epigastric vessels and rectus muscles.15

Clinical Presentation

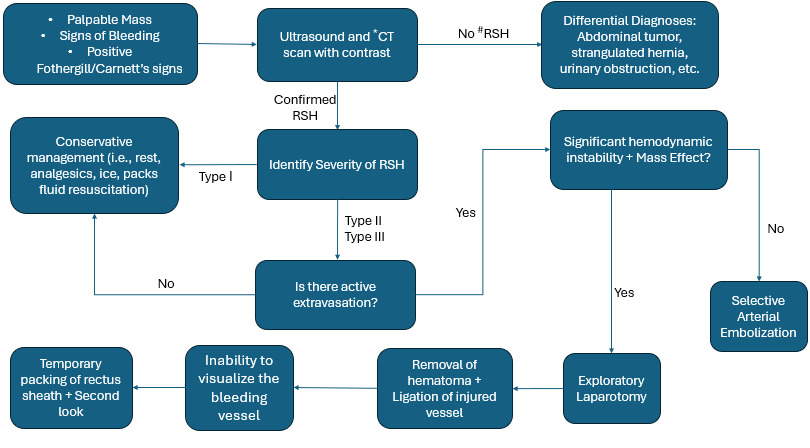

The physical presentation of RSH is similar to symptoms seen in various other conditions. Patients most often present with a palpable mass in their lower right quadrant. However, the hematoma can manifest in any of the abdominal quadrants. This mass may be with or without pain and might be accompanied by tenderness or guarding.16 Patients may also present with signs of bleeding. Drops in hematocrit and hemoglobin are indicative of bleeding and have been described in various cases of RSH.17,18 Ecchymosis has also been reported as a symptom in multiple cases of RSH.19,20 Other reported symptoms include abdominal swelling, fever, nausea, vomiting, rebound, tachycardia, fatigue, and syncope.21 Differentiating RSH from intra-abdominal pathologies include positive Fothergill’s and Carnett’s signs. Both are evaluated by laying the patient supine with their head elevated and abdominal muscles engaged. Fothergill’s sign is positive if the mass remains fixed and palpable when the rectus muscles are engaged. Carnett’s sign is positive if pain and tenderness increase with palpation while the rectus muscles are engaged. Positive Fothergill’s and Carnett’s signs indicate that the mass has an abdominal wall pathology rather than an intra-abdominal pathology.22 With the various symptoms that RSH presents, the differential diagnosis of RSH is included with conditions such as acute appendicitis, cholecystitis, biliary colic, urinary obstruction, abdominal tumors, strangulated hernia, and diverticulitis.1

Diagnosis

Once a mass is identified through a physical examination, ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) are utilized to identify the pathology of the mass. Ultrasound can be a useful first-line method of screening to quickly identify a mass. RSH will present as spindle shaped on longitudinal scans and will be ovoid on transverse and coronal scans. Abdominal ultrasound has an 80-90% sensitivity, which may lead to issues accurately identifying the origin of the mass.1 CT scans are the most common method of identifying RSH because of the high sensitivity and specificity. CT scans reveal information about the size, origin, location, and extent of the hematoma which are vital in the classification and treatment of RSH.1 In 1996 Berna et al. conducted a retrospective study where they described a 3-type classification system for RSH. Type I hematomas are the least severe with the mass being contained intramuscular with an increase in muscle size. The hematoma is unilateral with no dissection through the fascial planes. Type II hematomas are moderately severe and are still contained intramuscularly but have bleeding between the rectus muscle and transversalis fascia. However, type II do not have any invasion into the pre-vesical space. Type III are the most severe and may not affect the muscle, but there will be bleeding between the rectus muscle and transversalis fascia. There also will be blood occupying the pre-vesical space and potentially entering the peritoneum. In some cases, type III hematomas may result in hemoperitoneum.23 Type I hematomas tend to have the best prognosis and often do not need hospitalization or surgical intervention. Type II and III hematomas are more severe and can require hospitalization. In severe cases where hemodynamic stability is unachievable surgical intervention may be necessary.23 Table 1 outlines Berna classification of RSH and the corresponding treatments.

Treatment

Treatment option depends on the severity of the hematoma and the hemodynamic stability of the patient. RSH is generally self-limiting but can potentially be fatal. The most recent publication identified a mortality rate at about 2% for patients with RSH.9 First-line treatment for all RSH is conservative management. This may include rest, analgesics, hematoma compression, ice packs, treatment of predisposing conditions, fluid resuscitation, reversal of anticoagulation therapies, and blood transfusions. Anticoagulant therapies should be held until hemodynamic stability has been achieved. Vitamin K can be used to correct coagulopathies once anticoagulants are discontinued.21 Many RSH cases will be corrected through medical management, but studies have identified risk factors that are predictive of conservative treatment failure. Contrella et al. identified active extravasation on CT, hematoma volume of greater than 1300 mL, hemoglobin decrease greater than 0.25 g/dL/h, and greater than 4 units of red blood cells transfused as risk factors for conservative treatment failure.24 Similarly, Fimbres et al. also identified active extravasation and hematoma volume as strong predictors of conservative treatment failure.25

When hemodynamic stability is unachievable through medical management, targeted arterial embolization becomes the next line of treatment. Transarterial embolization is generally used before surgery due to the less invasive nature and the low risk of complications. This intervention is used for patients displaying persistent hemodynamic instability with a drop in Hg values greater than 2 g/dL after 3 hours post-reversal of anticoagulant therapy. It is also indicated for Berna type III RSH with active extravasation upon CT angiogram (CTA) and patients with bleeding following trauma or iatrogenic injury.22 Arterial embolization is typically performed by interventional radiologists and includes the use of catheters with fluoroscopy guidance to specifically target the vessels of interest. Semeraro et al. describes using a .35" hydrophilic guide wire and Cobra or J-curve guiding catheters to cannulate the artery of interest using fluoroscopy guidance. They injected 8 mL of iodinated contrast in the catheter to visualize the surrounding vessels and use a 2.7-Fr Progreat microcatheter to selectively access the targeted artery.22 Bleeds originating from the inferior epigastric artery were approached using a contralateral 6-Fr femoral arterial puncture with crossover technique. This allowed for the external iliac artery and inferior epigastric artery to be accessed and catheterized. Microcatheterization of the inferior epigastric artery was performed to stop the bleeding, but if microcatheterization was unachievable they would place the catheter in a proximal position in the main artery. Bleeding from the superior epigastric artery was addressed through a common femoral approach placing the microcatheter as close as possible to the origin of the bleed.22

Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) and CTA are both frequently used in selective arterial embolization to accurately identify the source of the bleeding.26,27 In certain cases, clinicians may pursue embolization without specific angiographic proof of extravasation, which is described as blind embolization. Embolization of vessels with direct or indirect signs of active bleeding upon DSA is known as targeted embolization. Tiralongo et al. did not identify any significant differences between the two approaches in their retrospective study with both groups displaying an 86% clinical success rate.27 Embolization is also performed with a variety of embolic agents, which are used depending on the preference of the provider and the anatomy of the patient. These agents are classified as temporary, permanent, solid, liquid, alone, or in combination. Some examples are pushable or detachable coils, re-absorbable gelatin sponge, solid polyvinyl alcohol, hydrophobic injectable liquids, and liquid agents. Some of these are used in combination, such as coils and sponge, to best stop the bleeding.27 Semeraro et al. describes the use of glue diluted with ethiodized oil as an embolic agent. By utilizing varying ratios of glue to oil, they can adjust the polymerization time to allow the operator to embolize more distal or proximal. The liquid nature of the glue provides maneuverability that other solid materials may lack, which allows for access to small and irregular arterial branches. However, there are potential complications to using glue such as microcatheter entrapment or reflux of glue. Microcatheter entrapment is rare and often does not tend to lead to adverse clinical consequences, but reflux of glue can potentially occlude normal arterial territory and lead to downstream ischemic complications.22,28 With various embolic agents and methods of approach, targeted arterial embolization is a highly successful intervention for treating RSH. The overall technical success rate of transarterial embolization in Tiralongo et al. was 99%, which closely matches the 100% hemostasis rate displayed in Rimolea et al. and Semeraro et al.22,26,27

In RSH with significant hemodynamic instability and potential mass effect, surgical intervention may be necessary. Invasion of the hematoma into the pre-peritoneal and retroperitoneal space can drastically increase intra-abdominal pressure leading to organ failure from abdominal compartment syndrome.5,6,18 Doğan et al. describes a RSH extending into the peritoneal cavity that resulted in intraperitoneal bleeding.14 Surgical intervention often includes laparotomy to visualize and remove the hematoma combined with ligation of the bleeding artery.15 When no bleeding vessel if identified, temporary packing of the rectus sheath with a planned second-look exploration is a safe approach.29 In cases where mass effect is present, excision of ischemic and necrotic tissue and rectus muscles fibers may be necessary.6,18 Chamsy et al. describes a case of preperitoneal RSH treated with laparoscopic drainage. In this case, the patient previously underwent a total laparoscopic hysterectomy, which resulted in damaged muscles and small blood vessels. The subfascial and preperitoneal location of this RSH made the laparoscopic approach accessible and allowed for the aspiration of 250 mL of viscous blood and irrigation of the hematoma cavity.30 Some clinicians may place a Jackson-Pratt drain to drain fluid and blood clots from the hematoma cavity.14,30 Surgical intervention should not be considered for minor RSHs that are self-limiting. Unnecessary laparotomy can interfere with the tamponade and lead to continued bleeding.18

Conclusion

Patients on anticoagulants presenting with palpable abdominal masses and symptoms of bleeding should have RSH considered within their differential diagnosis. If RSH is identified, conservative management should be the first line of treatment, followed by percutaneous arterial embolization. Surgery should be the last line of treatment and reserved for cases where the hematoma extends into the preperitoneal or retroperitoneal space and affects other structures within the abdomen. Surgical intervention includes drainage and removal of the hematoma alongside ligation of the affected arteries. With increased chronic anticoagulant use, surgeons may see RSH more frequently than before and, therefore, they should maintain a high index of suspicion for RSH and be prepared to diagnose and treat this condition.

_and_inferior_e.png)

_and_inferior_e.png)