Introduction

Visceral artery pseudoaneurysms (VAPAs) are an uncommon but well-recognised complication of pancreatitis, with an incidence reported between 0.1% and 4.3%. Despite their rarity, they carry a high risk of rupture and mortality.1,2 A pseudoaneurysm represents a contained arterial wall disruption with communication to the vessel lumen, in contrast to a true aneurysm, which involves dilatation of all layers of the arterial wall. In pancreatitis, pseudoaneurysms account for the majority of arterial haemorrhagic complications.3

The pathogenesis is thought to involve enzymatic autodigestion, inflammation, and tissue necrosis leading to arterial wall erosion. Consequently, vessels adjacent to the pancreas—most commonly the splenic, gastroduodenal, and pancreaticoduodenal arteries—are typically affected. Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysms are particularly rare. Rupture may result in massive haemorrhage, with reported mortality rates of 25–50%, prompting recommendations for early intervention.2

Clinical presentation ranges from asymptomatic lesions to life-threatening haemorrhage. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography is commonly used for diagnosis, while angiography remains the gold standard due to its superior sensitivity and therapeutic capability.4 Management has evolved from open surgery to predominantly endovascular approaches; however, intervention may carry significant risk when pseudoaneurysms involve non-expendable arteries or multiple vascular territories.5,6 Due to their rarity, no consensus guidelines exist regarding the optimal management or surveillance of visceral pseudoaneurysms.

This report describes a rare case of multiple hepatic artery and coeliac trunk pseudoaneurysms following severe necrotizing pancreatitis that were successfully managed with conservative surveillance alone.

Case Report

A 67-year-old woman presented to a peripheral hospital with acute epigastric pain and was initially managed for presumed biliary colic. During admission, she acutely deteriorated, developing tachypnoea with a respiratory rate of 35 breaths per minute, drowsiness, and clinical features of sepsis. Repeat laboratory investigations demonstrated a leukocytosis with a white cell count of 15.1 × 10⁹/L, a rising serum bilirubin of 90 μmol/L, and markedly deranged liver function tests (ALT 515 U/L, AST 450 U/L, GGT 456 U/L, ALP 186 U/L). A diagnosis of acute cholangitis was made, and she was transferred to our tertiary centre for urgent endoscopic intervention.

An emergency endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed. No choledocholithiasis was identified; however, the bile duct effluent appeared turbid, consistent with biliary sepsis. A double-ended pigtail biliary stent was inserted to facilitate drainage. Following the procedure, her liver function tests improved promptly.

Despite biochemical improvement, the patient’s clinical course was complicated by persistent systemic inflammation and escalating abdominal pain. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated features consistent with severe acute necrotizing pancreatitis, including extensive pancreatic oedema, areas of hypo-enhancement, marked peripancreatic fat stranding, and multiple peripancreatic fluid collections. The largest collection measured approximately 10 × 15 × 5 cm (Figure 1).

Ten days following initial presentation, the patient was referred for endoscopic drainage of the peripancreatic fluid collections. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage was performed with insertion of a lumen-apposing metal stent (AXIOS) and an additional plastic stent into the largest collection. A repeat contrast-enhanced CT scan was recommended two weeks following stent placement to assess treatment response (figure 2).

On this interval CT imaging, the distal common hepatic artery (CHA) and the proximal left (LHA) and right hepatic arteries (RHA) were noted to be non-opacified, with soft tissue attenuation tracking along the expected course of these vessels. In the clinical context, these findings were most consistent with arterial thrombosis with associated vessel expansion or pseudoaneurysm formation, giving rise to the observed imaging appearance.

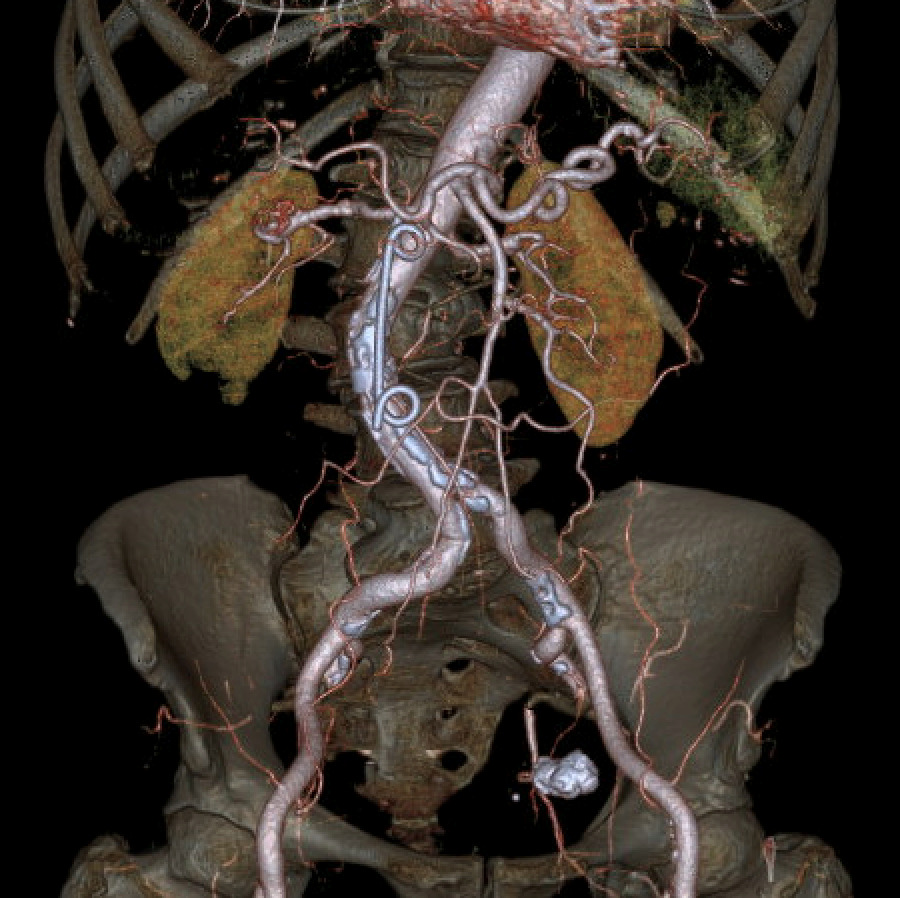

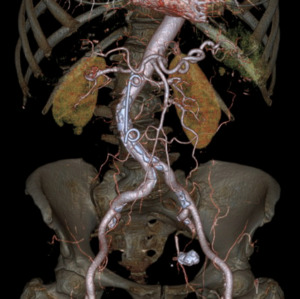

Further evaluation with Doppler ultrasound demonstrated non-occlusive bland thrombus within the common hepatic and left hepatic arteries. A subsequent CT angiogram (CTA), performed four weeks after the initial CT, confirmed the presence of multiple visceral pseudoaneurysms involving the hepatic arterial system. These included aneurysms of the right hepatic artery measuring 5.5 mm and 5.8 mm, intermediate hepatic artery aneurysms measuring 7.7 mm, 5.7 mm, and 14 mm, and a left hepatic artery aneurysm measuring 10.4 mm. Additionally, the coeliac trunk appeared diffusely aneurysmal with associated luminal irregularity (figure 3). All aneurysms demonstrated interval enlargement compared with prior imaging (Figure 2). Notably, during this period, the patient’s inflammatory markers and liver function tests had normalised.

Two weeks later, a repeat CTA demonstrated interval resolution of the previously identified pseudoaneurysms arising from the right, intermediate, and left hepatic arteries. The right and intermediate hepatic arteries were of markedly reduced calibre and tapered shortly after their origins, suggesting proximal arterial occlusion. The absence of contrast opacification within the previously visualised aneurysms was attributed to occlusion of the feeding vessels. Peripancreatic inflammatory stranding had mildly improved, and the previously noted lesser sac collection was no longer visualised (Figure 4).

The patient was managed conservatively with close radiological surveillance with a CT scan at three and nine and 15weeks after this scan. These scans demonstrated no change in the appearance of the hepatic arteries. During this interval, the AXIOS stent and peripancreatic drains were removed without complication.

Final follow-up CT imaging, performed 4.5 months after initial presentation, demonstrated only mild irregularity of the left hepatic artery with a small 2 mm fusiform dilatation. There was minimal residual irregularity along the inferior aspect of the common hepatic artery and a small, thick-walled residual fluid collection measuring approximately 1 cm located between the pancreatic neck and stomach. No new vascular abnormalities were identified (figure 5).

Four weeks later, the patient underwent an elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy without complication. The plastic biliary stent was removed two months following cholecystectomy. At nine months following initial presentation and eight months after the diagnosis of visceral pseudoaneurysms, the patient remains asymptomatic, with no further complications and has returned to normal activities of daily living.

Discussion

This case describes a rare presentation of multiple pseudoaneurysms involving the hepatic arterial system and coeliac trunk following severe necrotizing pancreatitis. While visceral pseudoaneurysms are a recognised complication of pancreatitis, hepatic artery involvement is exceptionally uncommon, particularly when multiple branches are affected simultaneously.7

Urgent intervention has traditionally been advocated due to the risk of rupture; however, management becomes challenging when pseudoaneurysms involve non-expendable arteries such as the hepatic arteries. Endovascular treatment, although effective in many cases, may result in hepatic ischaemia, biliary injury, or liver failure when multiple hepatic branches are compromised. Additional risks include intraprocedural rupture, non-target embolisation, infection, and delayed reconstitution of flow.

There is limited evidence suggesting that some asymptomatic hepatic pseudoaneurysms may undergo spontaneous thrombosis.8 Small paediatric series and isolated adult case reports have documented spontaneous resolution with conservative management and close imaging surveillance. Proposed criteria for non-operative management include small pseudoaneurysm size (<10mm), absence of symptoms or bile leakage, and stability or reduction in size on interval imaging.9 However, the true incidence of spontaneous thrombosis and predictors of rupture remain poorly defined.

In this case, conservative management was chosen due to clinical stability, normalisation of biochemical markers, relatively small pseudoaneurysm size, and the high procedural risk associated with intervention in the setting of multi-vessel involvement. Serial CT angiography demonstrated spontaneous thrombosis and complete resolution of the pseudoaneurysms without complication.

This case supports the consideration of conservative management in highly selected, asymptomatic patients with hepatic artery pseudoaneurysms, provided that close multidisciplinary oversight and rigorous radiological surveillance are maintained. Nevertheless, given the unpredictable natural history and potentially catastrophic consequences of rupture, non-operative management cannot be routinely recommended and should be reserved for carefully selected cases

_and_axial_(b)_ct_scan_images_demonstrating_significant_pancreatic_necrosis_and.png)

_and_axial_(b)_ct_images_demonstrating_the_lack_of_contrast_in_and_soft_tissue_.png)

_and_.png)

_and_left_(b)_hepatic_arte.png)

_and_axial_(b)_ct_scan_images_demonstrating_significant_pancreatic_necrosis_and.png)

_and_axial_(b)_ct_images_demonstrating_the_lack_of_contrast_in_and_soft_tissue_.png)

_and_.png)

_and_left_(b)_hepatic_arte.png)