Introduction

Diversion of the fecal tract is a common surgical procedure used to treat a variety of gastrointestinal conditions.1 These procedures often result in the creation of a Hartmann’s pouch. The separation of this segment of colon from the fecal stream can lead to inflammation, known as diversion colitis (DC). Many patients that develop DC will be asymptomatic, but the symptoms that develop because of DC can be distressing for the patient. The etiology of this inflammation is not definitively understood, with multiple hypotheses guiding a variety of treatment approaches. We report a case of symptomatic diversion colitis treated with a combination of antibiotics and mesalamine.

Case Description

Patient is a 78-year-old male who underwent a laparoscopic sigmoid resection and colostomy creation for neurogenic bowel. Three weeks after the surgery he presented to the outpatient surgery clinic with increased clear mucous drainage from the anus, which began when he started antibiotics for a concurrent urinary tract infection. Once the patient finished his current antibiotic regiment, he was recommended Cipro/Flagyl to treat suspected pouchitis.

The patient was on multiple medications that interfere with Cipro, so he was prescribed Flagyl and a mesalamine suppository for every 12 hours for 14 days. However, due to an inability to administer a suppository because of his tetraplegia, the patient was prescribed oral mesalamine three times a day for 14 days.

Upon a two-week follow-up, the patient reported complete resolution of mucus drainage after the treatment with oral mesalamine. However, the patient called two weeks later reporting recurrence of the anal discharge after running out of mesalamine. The oral mesalamine prescription was renewed, and the patient reported complete resolution of mucous drainage during the one-month follow-up visit.

Discussion

Surgical diversion of the fecal tract is a common procedure used to treat gastrointestinal malignancy, traumatic injury to the intestinal tract, colon obstruction, inflammatory bowel disease, or in our case neurogenic bowel.1 In a Hartmann’s procedure, the proximal end of the resected colon is brought up to the abdominal wall to form a colostomy, and the distal end is closed and left in place as a nonfunctional stump.2 This nonfunctional stump is susceptible to inflammation, known as diversion colitis (DC). Studies have identified endoscopic evidence of colitis in the nonfunctional stump of between 70% to 91% of patients who had undergone a diversion colostomy creation.3,4 Many patients with endoscopic evidence of diversion colitis may be asymptomatic. In Whelan et al. they only identified symptoms in only 6% of their patients.3 However, they did not classify infrequent mucous discharge as a significant symptom. In contrast, Ma et al. identified symptoms in 33% of their patients.5 Overall, patients that have undergone Hartmann’s procedure are at a high risk of developing diversion colitis, but many may not display any symptoms.

The pathophysiology of DC is still heavily debated, but it has been hypothesized that inflammation is due to bacterial overgrowth.6 Studies have identified less anaerobic flora and a higher percentage of nitrate-reducing bacteria in the diverted segment compared to the fecal tract.7,8 This may lead to a reduction in the production of short chain fatty acids (SCFAs). The diverted segment also does not have contact with the fecal stream, which leads to a deficiency of SCFAs and other nutrients for those colonocytes and microbes.9 Another hypothesis for etiology of diversion colitis is ischemia due to increased colonic artery resistance because of decreased SCFAs in the diverted colon segment.9 Despite the varied hypotheses, SCFA deficiency plays a major role in the development of diversion colitis. Butyrate, a SCFA, is the main fuel source for colonocytes and plays a direct role in mitigating chronic inflammation through its histone deacetylase inhibitory activity.10

DC is often asymptomatic, but can present as abdominal pain, anorectal pain, tenesmus, rectal bleeding, and mucosal discharge. Symptoms tend to manifest between 3 to 36 months after colostomy formation.4 Diagnosis of DC heavily relies on the clinical presentation of the patient combined with history of diversion colostomy or ileostomy. In our case, the patient presented with anal mucosal drainage during the post-operative period of a diversion colostomy. Differential diagnoses of DC are irritable pouch syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, or other etiologies of colitis.11 Endoscopic and histological confirmation of DC has been reported, but in our case the diagnosis of DC was made based on symptoms and surgical history.5,12

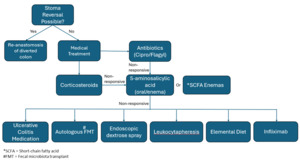

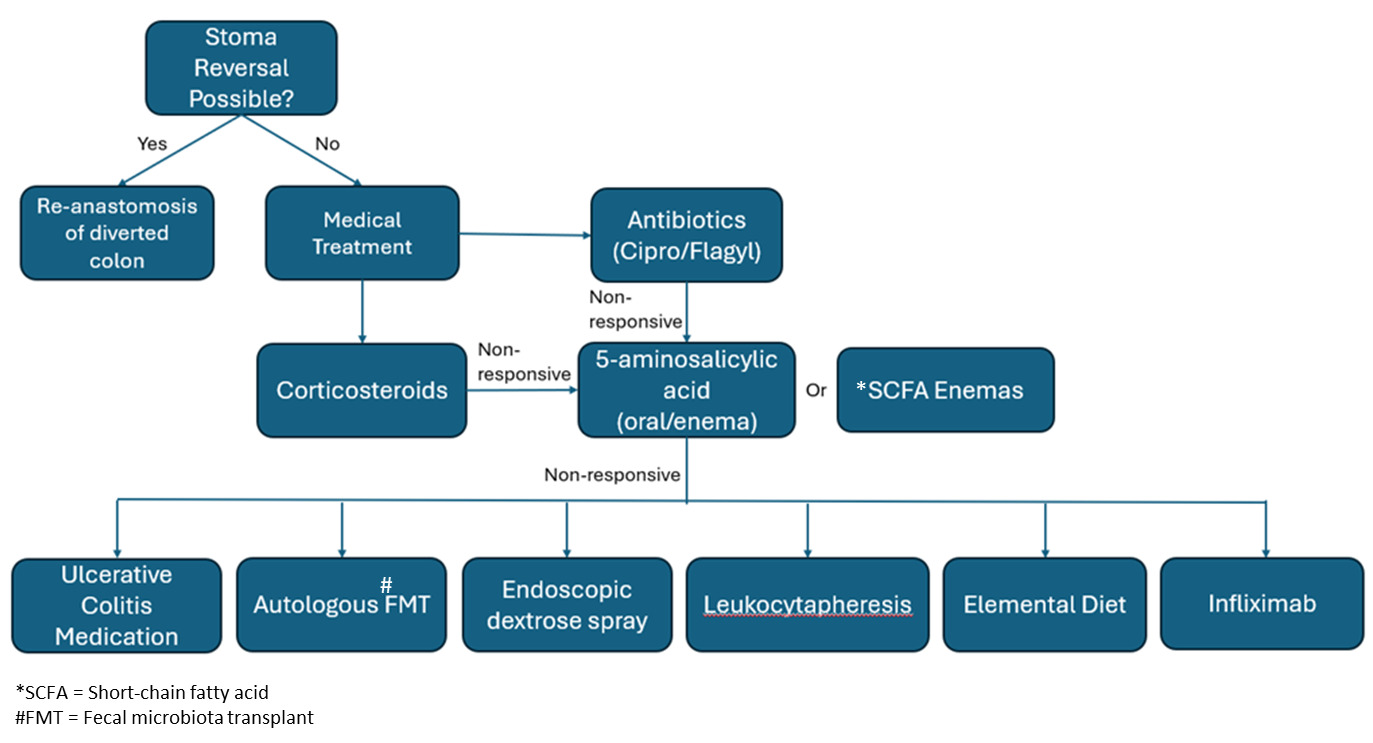

There are various approaches to treatment of DC since there is no established standard treatment. Surgical treatment of DC includes reversal of the diversion and re-establishment of the fecal stream or resection of the diverted segment.4,13 Resection is not often performed and is reserved for complications of DC such as uncontrolled perianal sepsis, perianal fistulous disease, or incontinence.4 Re-anastomosis of the diverted colon is ideal, but it may not be possible for patients who require a permanent stoma. For the individuals contraindicated for surgical treatment primary prophylactic treatment such as probiotics, sulfasalazine, immunomodulators, and cyclosporine may be used to prevent the development of DC post-operatively.14 Upon development of symptomatic DC, antibiotics are often the first line of treatment. A combination of ciprofloxacin and metronidazole has been shown to be effective in treating acute pouchitis, which may be useful for treating acute DC.14 Corticosteroids also have been used in cases where first-line antibiotics do not completely resolve the symptoms.14 SCFA enemas, primarily butyrate, have been investigated as a potential treatment for diversion colitis by supplementing the colonocytes with the SCFA’s that are not being produced due to the diversion of the fecal stream.4 Alternatively, 5-aminosalicylic acid, either orally or through an enema has been used to treat diversion colitis. It is primarily indicated for treatment of ulcerative colitis, but multiple case reports have displayed its efficacy in treating diversion colitis.11 In our case, the patient was prescribed metronidazole and oral mesalamine, which resulted in complete resolution of symptoms at the one-month clinic visit. Other treatments for ulcerative colitis with biological agents such as alicaforsen, tofacitinib, ustekinumab, and vedolizumab have also been explored as possible pharmacotherapies for chronic diversion colitis.14 These therapies all interfere with the inflammatory response that causes ulcerative colitis and may play a role in mitigating the inflammation of diversion colitis. Autologous fecal microbiota transplants (FMT) have also been explored as a method of treating DC by restoring the microbiome that was disrupted by the interruption of the fecal stream. FMT has been shown to increase the ratio of anaerobic bacteria to aerobic bacteria in the diverted colon.15 Autologous FMT is a newer treatment for DC compared to other treatments which have been studied more extensively such as SFCA enemas, antibiotics, and 5-aminosalicylic acid. Therefore, autologous FMTs may be used when other methods of treatment fail to completely resolve symptoms.16 Figure 1 displays a proposed algorithm for treating DC. Other therapies such as infliximab, leukocytapheresis, endoscopic dextrose spray, coconut oil enemas, and an elemental diet have been reported, but no extensive studies have been done to completely confirm their efficacy.11

Conclusion

Patients that have undergone Hartmann’s procedure are at a high risk of developing DC. Currently, the etiology of DC is still heavily debated, with hypotheses including microbiome disruption and SCFA deficiency. Without a completely understood etiology, there is no standardized treatment for DC. The first line of treatment is re-establishment of the fecal stream through surgical re-anastomosis of the diverted colon. However, patients that are contraindicated for surgical intervention require medical therapy. First line treatments include antibiotics and corticosteroids, followed by 5-aminosalicylic acid, ulcerative colitis medications, and SCFA enemas if the first-line treatments fail. Other therapies that have been explored include FMT, IBD medications, and elemental diets. Without a definitive understanding of the etiology of DC, it is difficult to establish a standard treatment plan. Therefore, it is integral for the provider to understand each avenue of treatment for patients suffering from symptomatic DC.