Introduction

Castleman disease is a rare lymphoproliferative disorder categorized into different clinical subtypes based on histopathology and symptomatology. The disease is broadly classified into unicentric and multicentric types, depending on the number of enlarged lymph nodes.1,2 Further subclassification includes histopathologic variants: hyaline vascular, plasma cell, and mixed.3 Multicentric Castleman disease (MCD) involves systemic inflammation, reactive proliferation of morphologically benign lymphocytes4–6 and can be further categorized into POEMS and TAFRO subtypes, though other variants are suspected.2,7–9

POEMS is characterized by Polyneuropathy, Organomegaly, Endocrinopathy, Monoclonal gammopathy, and Skin changes,8 while TAFRO includes Thrombocytopenia, Anasarca, myelofibrosis, Renal dysfunction, and Organomegaly.2,7,9 MCD is driven by either infectious or idiopathic mechanisms.10 Over 50% of MCD cases are associated with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8).10 Idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease (iMCD) lacks a known viral etiology but involves inflammatory cytokines, particularly IL-6, although its pathogenesis and natural history remain poorly understood.11,12

Here, we describe a unique case of iMCD, the plasma cell variant, in a patient presenting with typical features of Castleman disease combined with extensive intraabdominal lymphadenopathy, peritonitis, and sepsis.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old African American male with a past medical history of iMCD (plasma variant), hemolytic anemia, gunshot wound to lower left extremity, and deep venous thrombosis presented to the emergency department with constant, diffuse abdominal pain associated with nausea, vomiting, tachycardia, and shortness of breath. The patient had previously received care for his iMCD at an outside institution and was being treated with siluximab but the patient had no follow-up in approximately one year and was not on any therapeutic regimens for that duration.

Upon initial presentation, the patient appeared diaphoretic, with increased respiratory effort, a diminished radial pulse, and lower abdominal tenderness to palpation with guarding. The patient was tachycardic, hypotensive, and exhibited decreased oxygen saturation. Blood work demonstrated severe leukocytosis, marked thrombocytosis, mild anemia, hyponatremia, hypoalbumenia, and lactic acidosis. A chest CT demonstrated extensive bilateral axillary, mediastinal hilar and subcarinal lymphadenopathy, large bleb formation suggestive of severe interstitial lung disease. The abdominal CT revealed severe abdominopelvic ascites with diffuse peritoneal enhancement, multiple loculated rim enhancing collections, diffusely ischemic small bowel, diffuse colonic and esophageal wall thickening, diffuse mesenteric edema, inferior vena cava compression, and free intraabdominal fluid.

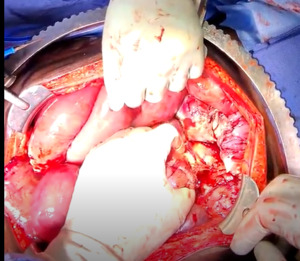

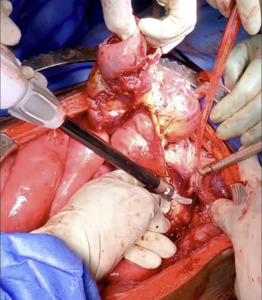

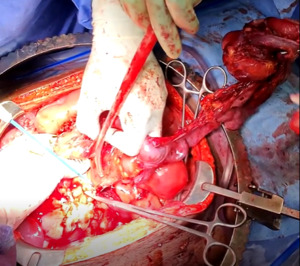

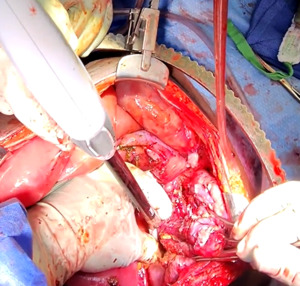

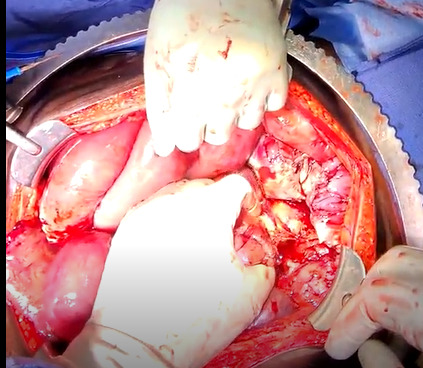

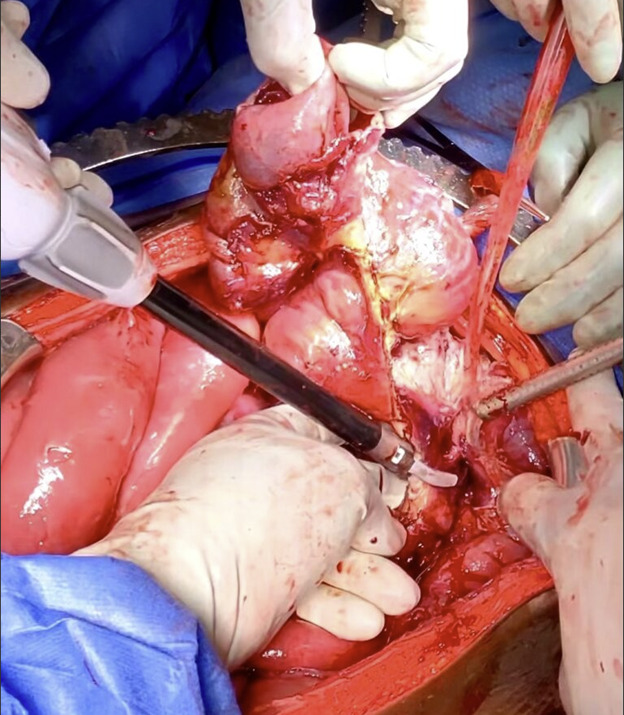

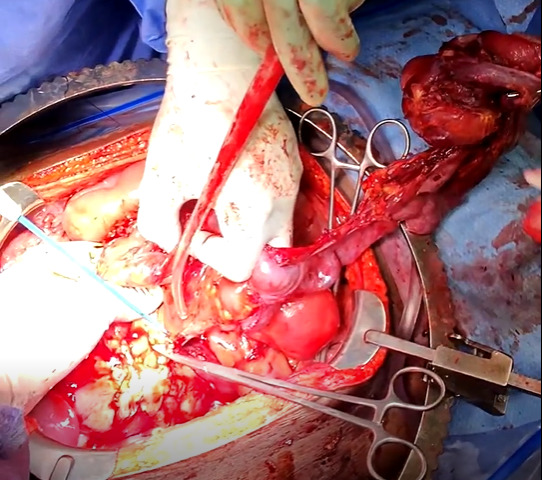

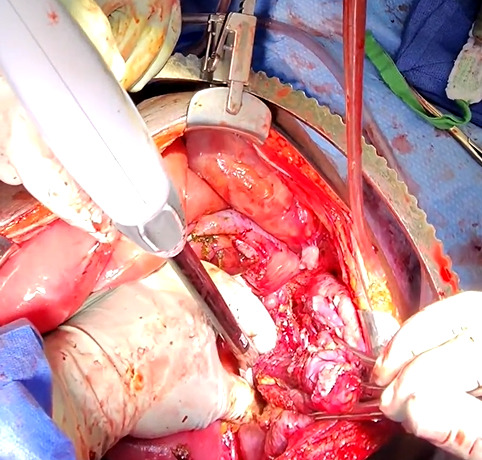

The patient was taken to the operating room for an emergent laparotomy supported with large-volume intravenous fluids and vasopressors. Findings at the time of operation included extensive edema and adhesions involving small and large bowel loops as well as extensive retroperitoneal infiltration of the mesentery, ischemia of a long segment of distal ileum involving the cecum and ascending colon, and extensive raw surface scar adhesions in the retroperitoneum and mesentery. The distal ileum was resected and left in discontinuity. A right hemi-colectomy was performed including a perforated appendix left in discontinuity. Extensive interloop adhesiolysis was performed between small and large bowel loops. Substantial washout was performed for mitigation of peritonitis associated with purulence found in all four abdominal quadrants. Laparotomy pads were left in the patient for damage control, and with a plan to return to the OR in 24 hours after guided resuscitation. The patient received two units of packed red blood cells during the operation. The patient was admitted to the surgical intensive care unit (SICU) for septic resuscitation and to monitor hemodynamic status. Arterial blood gas indicated a mixed respiratory and metabolic acidosis. He remained intubated, sedated, tachycardic, and hypotensive on vasopressors. 24 hours later, the patient underwent a reopen exploratory laparotomy. Additional adhesiolysis and washout were performed along with terminal ileal small bowel resection. A small portion of the omentum was identified as devitalized and was removed. Two small bowel serosal injuries were repaired; an end ileostomy was created with midline abdominal closure.

Post-operatively, the patient improved significantly and remained afebrile and hemodynamically normal. During his stay, the patient completed a full antibiotic course including Zosyn and Vancomycin. He transitioned to a regular diet and had adequate urine output. Hematology and oncology were consulted, and the patient was started on prednisone 40 mg daily with Bactrim TID. The patient continued to improve with outpatient visits and plans to reestablish care with his original hematology/oncology team to restart siluximab.

Discussion

The severe intraabdominal manifestations observed in this case of iMCD, plasma cell variant, highlight the atypical features that can complicate Castleman disease and challenge our understanding of its pathophysiology and natural history. As demonstrated in this patient, regular follow-up and adherence to updated international guidelines and therapies including those targeting IL-6 such as siluximab are imperative to reducing disease burden; in this case the extensive lymphadenopathy demonstrated after approximately one year of medical non-compliance.

Conclusion

This case of potentially fatal, atypical intraabdominal features emphasizes the importance of recognizing Castleman disease in patients presenting with nonspecific and severe systemic symptoms. Early identification and comprehensive multidisciplinary management are vital for improving outcomes in this rare and poorly understood condition. Continued research and heightened clinical awareness will be essential in advancing our understanding and treatment of Castleman disease.