Introduction

Intracranial aneurysms predominantly occur at major arterial bifurcations near the circle of Willis, with approximately 85% located in the anterior circulation.1 Aneurysms of peripheral cortical branches represent only 2-5% of all intracranial aneurysms, and those involving the orbitofrontal artery are exceptionally rare.2 The orbitofrontal arteries typically arise from the A2 segment of the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) or the anterior communicating artery (AComm) complex and supply the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex.3

Anatomical variants of the orbitofrontal artery have been described, including rare origins from the A1 segment of the contralateral ACA.4 However, orbitofrontal branches arising from the middle cerebral artery (MCA) are extremely uncommon. The origin of OBFA aneurysms from the M1 segment of the MCA has not been previously documented in the available literature, making this case uniquely significant. Furthermore, such anomalous vascular variants appear to occur with notable frequency in Indian populations, necessitating increased awareness among neurosurgeons in this region.

We present a case of a ruptured saccular aneurysm arising from an orbitofrontal branch originating from the M1 segment of the MCA, treated successfully with microsurgical clipping.

Case Presentation

Clinical History and Examination

A 52-year-old male manual labourer presented to the emergency department with an 8-day history of progressively worsening headache and a 4-day history of vomiting. He denied loss of consciousness, seizures, or focal neurological deficits. His medical history was unremarkable with no significant comorbidities. There was no family history of intracranial aneurysms or vascular malformations.

On neurological examination, the patient was alert and oriented with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15. Cranial nerve examination, motor and sensory function, coordination, and gait were all normal. No meningeal signs were elicited. Based on clinical grading scales, the patient was classified as Hunt and Hess Grade 1, World Federation of Neurological Surgeons (WFNS) Grade 1, Prognosis on Admission of Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (PAASH) Grade 1, and Full Outline of UnResponsiveness (FOUR) score of 4, indicating excellent clinical status.

Neuroimaging

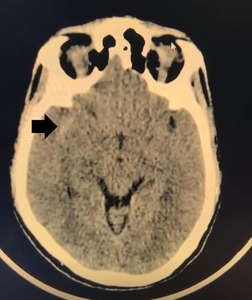

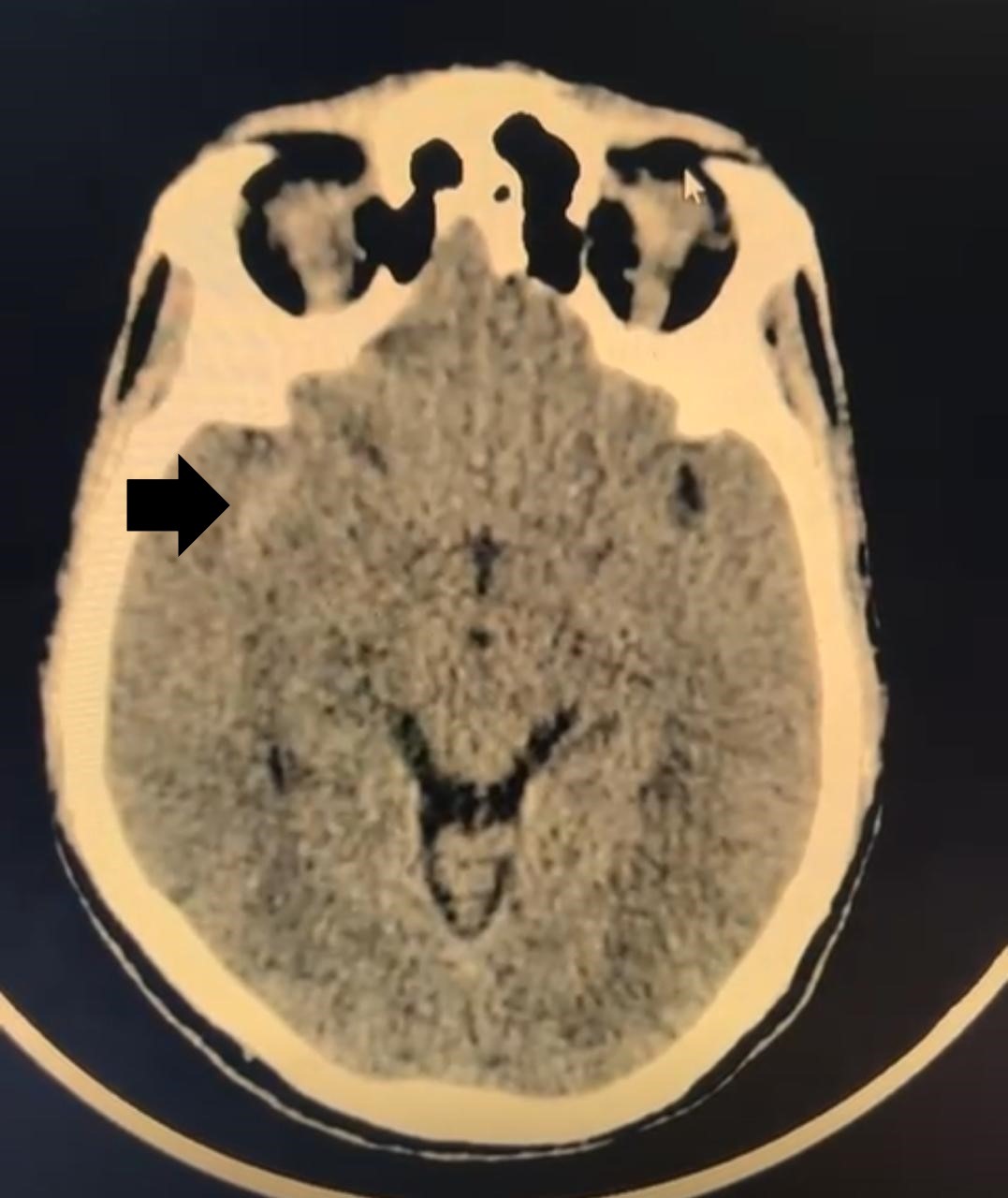

Non-contrast computed tomography (NCCT) of the brain revealed subarachnoid hemorrhage predominantly in the right sylvian fissure [Figure 1]. Hemorrhage grading scales indicated: Modified Fischer Scale 1, Classen Scale 1, and Hijdra Scale 0; indicating minimal blood burden with low risk for delayed cerebral ischemia and vasospasm. These favourable grading parameters not only suggested minimal vasospasm risk but also projected good functional prognosis.

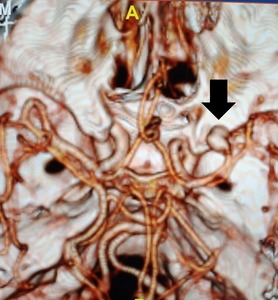

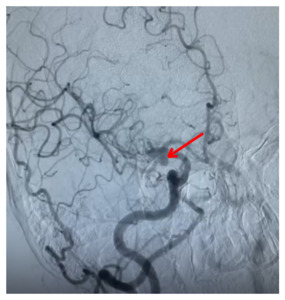

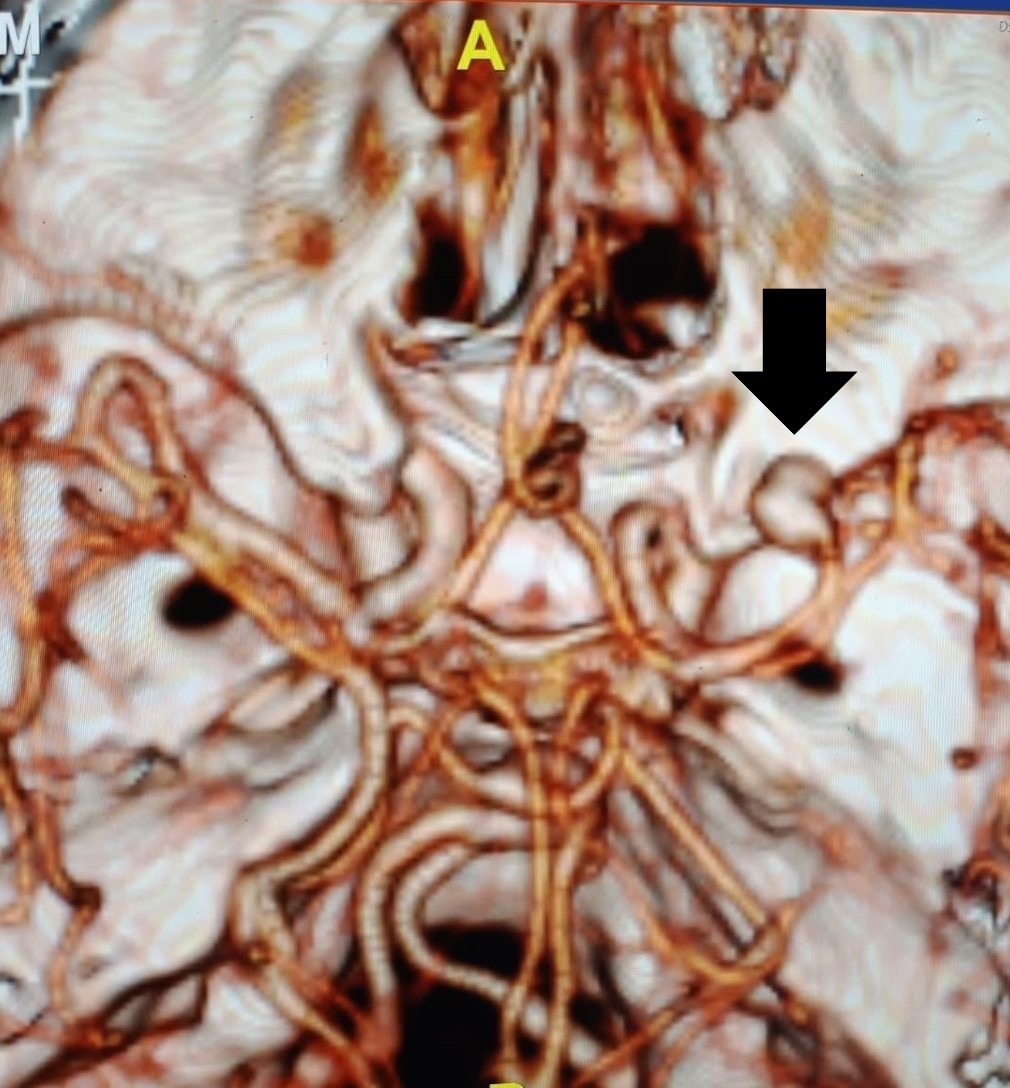

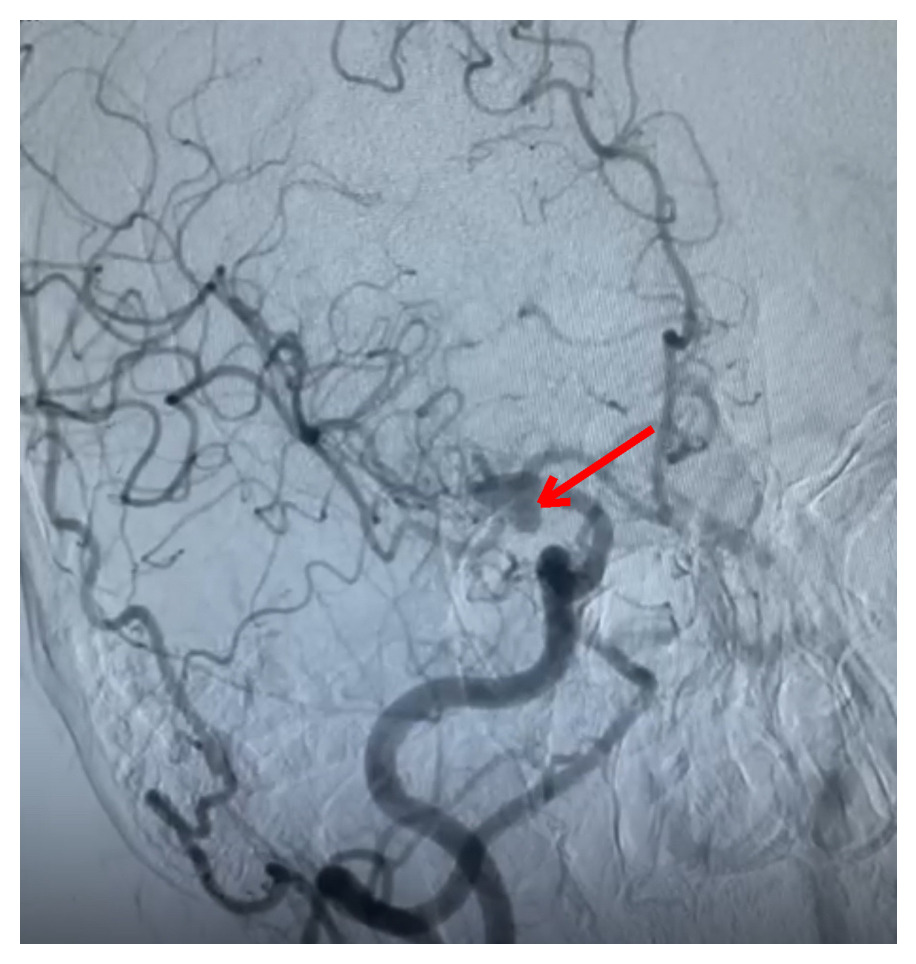

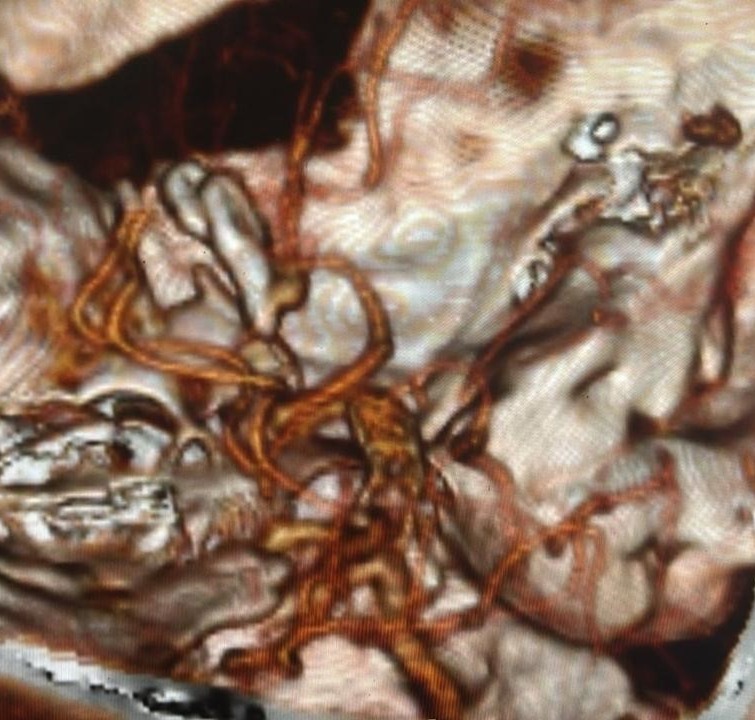

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) revealed an anomalous saccular aneurysm (7×5 mm) arising from the M1 segment of the right middle cerebral artery [Figure 2]. This finding was unusual as the branching artery demonstrated characteristics consistent with orbitofrontal artery territory supply. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) performed via right femoral approach using a JR 3.5 5F guide catheter confirmed a Type 3 aortic arch with the anomalous aneurysm location [Figure 3]. The aneurysm demonstrated a broad neck and favorable morphology for microsurgical intervention.

Surgical Management

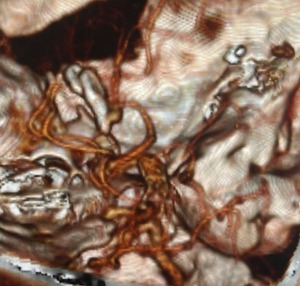

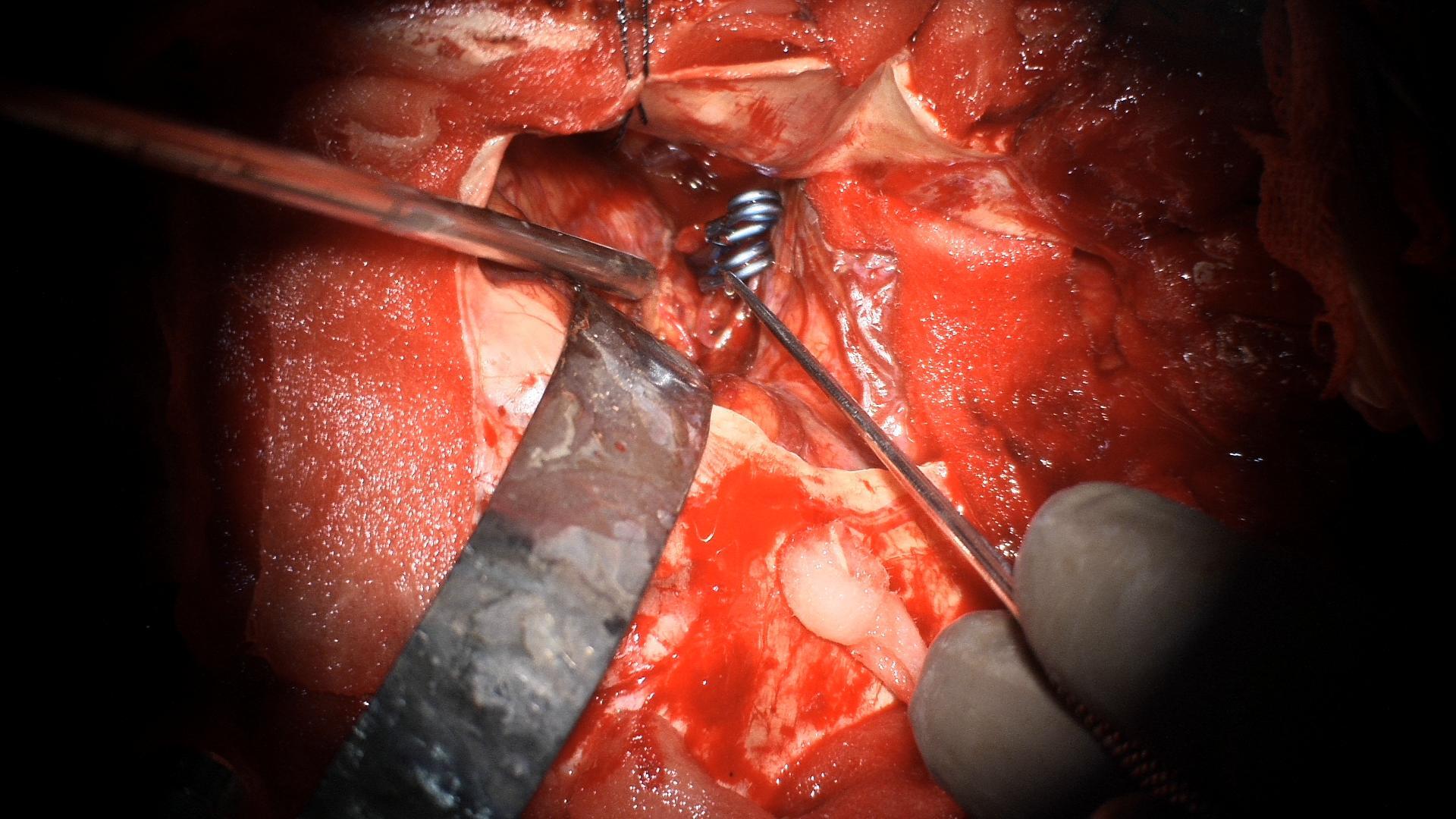

The patient underwent right pterional craniotomy under general anaesthesia. Standard microsurgical dissection along the sylvian fissure was performed. The M1 segment of the MCA was identified and followed distally. The anomalous orbitofrontal branch was identified arising from the superior aspect of the M1 segment. The saccular aneurysm arose from this branching point and measured approximately 7 mm in maximum diameter. The aneurysm neck was carefully dissected free from surrounding arachnoid adhesions and perforating vessels. Two titanium clips were applied across the aneurysm neck, achieving complete obliteration of the aneurysm while preserving the parent orbitofrontal artery and adjacent MCA branches [Figure 4]. Intraoperative indocyanine green (ICG) video angiography confirmed complete aneurysm occlusion with preserved flow in all adjacent vessels. The orbitofrontal artery was successfully preserved. The pterional exposure was adequate to visualize parent vessel anatomy and ensure optimal clip positioning. Hemostasis was achieved, and the craniotomy was closed in standard fashion.

Post-Operative Course and Outcome

Post-operative NCCT brain and CTA demonstrated complete aneurysm obliteration without residual filling or parent vessel compromise [Figure 5]. The patient was discharged on post-operative day 7 without neurological deficits. Clinical examination remained unremarkable on discharge, with intact higher mental functions. At weekly and subsequent monthly follow-up appointments, he remained neurologically intact without recurrent symptoms, vasospasm related complications and there was no evidence of delayed cerebral ischemia, hydrocephalus, or clip migration. Neuropsychological assessment revealed no cognitive deficits or frontal lobe dysfunction. Higher mental functions remained completely intact. At three-month follow-up, the patient had resumed occupational activities without restrictions.

Discussion

Anatomical Considerations

The orbitofrontal artery is a cortical branch of the anterior cerebral artery that supplies the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex, including the gyrus rectus and olfactory tract region.3 The medial and lateral orbitofrontal arteries typically arise from the A2 segment of the ACA, usually within 5 mm of the AComm junction, and course anteriorly over the gyrus rectus.5 Anatomical variants are well-documented in the anterior cerebral circulation, including anomalous origins of cortical branches.4,6

In rare instances, accessory or duplicate MCA branches can arise from the A1 or A2 segments of the ACA.7 These anomalous vessels represent phylogenetic remnants, as the MCA develops later than the ACA during embryogenesis and may be considered an early branch of the anterior cerebral circulation.8 Our case represents an even more unusual variant: an orbitofrontal branch arising directly from the M1 segment of the MCA rather than from the ACA-AComm complex. To our knowledge, this specific anatomical variant has not been previously reported in association with an aneurysm.

Aneurysm Formation and Rupture

The pathophysiology of aneurysm formation at unusual locations remains incompletely understood. Hemodynamic stress at arterial bifurcations, combined with structural weakness in the arterial wall, is thought to be the primary mechanism.9 Distal cortical branch aneurysms represent only 2-5% of all intracranial aneurysms and are often associated with underlying pathologies such as arteriovenous malformations, moyamoya disease, or previous trauma.2,10

Isolated orbitofrontal artery aneurysms are exceptionally rare. A comprehensive literature review reveals only a handful of reported cases. Kato et al. described a ruptured orbitofrontal artery aneurysm associated with a dural arteriovenous malformation (DAVM) in the anterior cranial fossa, which was successfully treated with microsurgical clipping.11 Xiaodong et al. reported the first case of an isolated, partially thrombosed orbitofrontal artery aneurysm that mimicked an A1 segment aneurysm, emphasizing the importance of high-resolution angiographic imaging for accurate diagnosis.12

In our patient, the aneurysm arose from an already anomalous vessel, suggesting that the anatomical variant itself may have contributed to abnormal hemodynamic stress and subsequent aneurysm formation. The absence of other vascular malformations, multiple aneurysms, or systemic risk factors suggests this was a true isolated peripheral aneurysm.

Relevance to Indian Neurosurgery

The apparent increased prevalence of anomalous OBFA aneurysms originating from the MCA in Indian populations warrants special attention. A landmark comprehensive anatomical investigation from Northern India has confirmed that OBFA frequently arises from the M1 segment, occurring in 75% of examined specimens, with a significant proportion (20%) representing the first cortical branch from M1.13 This anatomical predisposition may explain the increased incidence of OBFA aneurysms at this location within Indian populations. The earlier classification systems, which predominantly described OBFA as a branch of the M2 segment, may have underestimated the true frequency of M1 origin, particularly in Asian populations.13 Whether this represents true ethnic anatomical variation or heretofore unrecognized regional differences remains an important area for further investigation. Such variants warrant inclusion in neurovascular anatomy textbooks and educational curricula, particularly given their documented prevalence in Indian populations. Systematic documentation through multicentre registries would clarify the epidemiology and natural history of these anomalous variants. Such registries would facilitate accumulation of data regarding optimal management strategies and functional outcomes following intervention across diverse populations.

Clinical Presentation and Grading

Our patient presented with the classic symptoms of SAH: sudden-onset severe headache and vomiting. Despite the presence of blood in the sylvian fissure, his excellent clinical grade (Hunt & Hess 1, WFNS 1) reflects the limited haemorrhage burden and absence of significant intraventricular or intraparenchymal extension. This favourable presentation is consistent with low-volume SAH from small peripheral aneurysms.

The CT grading scales (Modified Fisher 1, Claassen 1, Hijdra 0) all indicated minimal blood burden, which correlates with lower risk of delayed cerebral ischemia, vasospasm, and hydrocephalus.14 This favourable radiographic profile, combined with excellent clinical grade, predicted the good outcome ultimately achieved.

Treatment Considerations

The management of peripheral anterior circulation aneurysms requires careful consideration of both surgical and endovascular approaches. The location and morphology of the aneurysm, parent vessel anatomy, and patient clinical status all influence treatment selection.15

Microsurgical clipping offers several advantages for peripherally located aneurysms: direct visualization of the aneurysm and parent vessels, ability to evacuate associated hematomas, and definitive treatment with low recurrence rates.16 The pterional approach provides excellent exposure of the sylvian fissure and proximal MCA segments. In our case, the superficial location of the M1 segment and the anterior projection of the aneurysm made microsurgical access straightforward.

Endovascular coiling represents an alternative for selected cases, particularly when the aneurysm-to-parent vessel ratio is favourable.15,17However, very small parent vessels and wide-necked morphology may limit endovascular treatment options for distal branch aneurysms. Advances in catheter technology and the availability of intracranial stents and flow diverters have expanded endovascular capabilities, but these devices are optimized for proximal rather than distal vessels.18

Preservation of the parent orbitofrontal artery was a key surgical objective in our case. While the functional consequences of sacrificing an orbitofrontal artery are not well-defined in the literature, potential complications may include olfactory dysfunction, prefrontal cognitive deficits, and behavioral changes related to orbitofrontal cortex damage.19 Successful clip application with preservation of parent vessel flow, confirmed by intraoperative ICG angiography, minimized the risk of postoperative ischemic complications.

Outcomes and Complications

Published outcomes for orbitofrontal artery aneurysms are generally favourable when diagnosed and treated appropriately. Kato et al. reported good recovery following clipping of a ruptured OFA aneurysm associated with DAVM.11 Xiaodong et al. similarly reported successful treatment of an isolated OFA aneurysm without complications.12

Potential complications specific to orbitofrontal region surgery include: rebleeding (if aneurysm is incompletely treated), frontal lobe contusion or edema, anosmia from olfactory tract injury, and vasospasm following SAH.20 Our patient experienced none of these complications, likely due to the minimal haemorrhage burden, careful microsurgical technique, and excellent baseline clinical status.

Long-term neuropsychological outcomes following treatment of orbitofrontal region aneurysms deserve special attention. The orbitofrontal cortex plays critical roles in executive function, decision-making, impulse control, and emotional regulation.21 Damage to this region, either from the haemorrhage itself or iatrogenic surgical injury, can produce subtle but significant behavioural changes known as orbitofrontal syndrome.22 Our patient’s normal neuropsychological assessment at follow-up suggests successful preservation of frontal lobe function.

Limitations and Future Directions

This case report has inherent limitations as a single-patient experience. The rarity of orbitofrontal artery aneurysms, particularly those arising from anomalous origins, precludes large-scale studies or meta-analyses. The true incidence, natural history, optimal treatment strategies, and long-term outcomes remain poorly defined.

Multicentre registries documenting rare intracranial aneurysm locations would be invaluable for accumulating sufficient cases to generate meaningful data.22 Such registries should include detailed anatomical descriptions, high-quality imaging, treatment approaches, and standardized long-term follow-up including neurocognitive assessment. Additionally, advanced imaging techniques such as 7-Tesla MRI and computational fluid dynamics modeling may provide insights into the hemodynamic factors contributing to aneurysm formation at unusual locations.

Conclusion

We present a rare case of ruptured saccular aneurysm arising from an orbitofrontal branch originating from the M1 segment of the middle cerebral artery. This case represents the first documented orbitofrontal artery aneurysm arising anomalously from the M1 segment of the middle cerebral artery. Recognition of such rare vascular variants is essential for contemporary neurosurgeons, particularly in Indian populations where these lesions may have increased prevalence. This case highlights several important clinical principles:

-

Peripheral cortical branch aneurysms, though rare, must be considered in the differential diagnosis of subarachnoid haemorrhage;

-

High-resolution vascular imaging including DSA is essential for accurate anatomical delineation;

-

Microsurgical treatment can achieve excellent outcomes when performed by experienced neurovascular surgeons;

-

Preservation of parent vessels supplying eloquent cortical regions should be prioritized when feasible.

This case adds to the limited published literature on orbitofrontal artery aneurysms and underscores the remarkable anatomical variability of the cerebral vasculature. As imaging technology advances and more cases are documented, our understanding of these rare vascular lesions will continue to evolve. Multicentre registries documenting the myriad locations of intracranial aneurysms will enhance understanding of these rare entities and guide future management strategies.