Introduction

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is one of the most performed surgical procedures worldwide. Dropped gallstones (DGs) can act as a nidus for chronic inflammation and infection, leading to complex presentations that may mimic peritoneal carcinomatosis or soft-tissue metastases. We report the case of a 64-year-old man with a history of cholecystectomy with gallstone spillage who developed recurrent peritoneal and abdominal wall abscesses due to retained gallstones two years after surgery, initially suspected to represent metastatic disease of unknown primary origin.

Case Summary

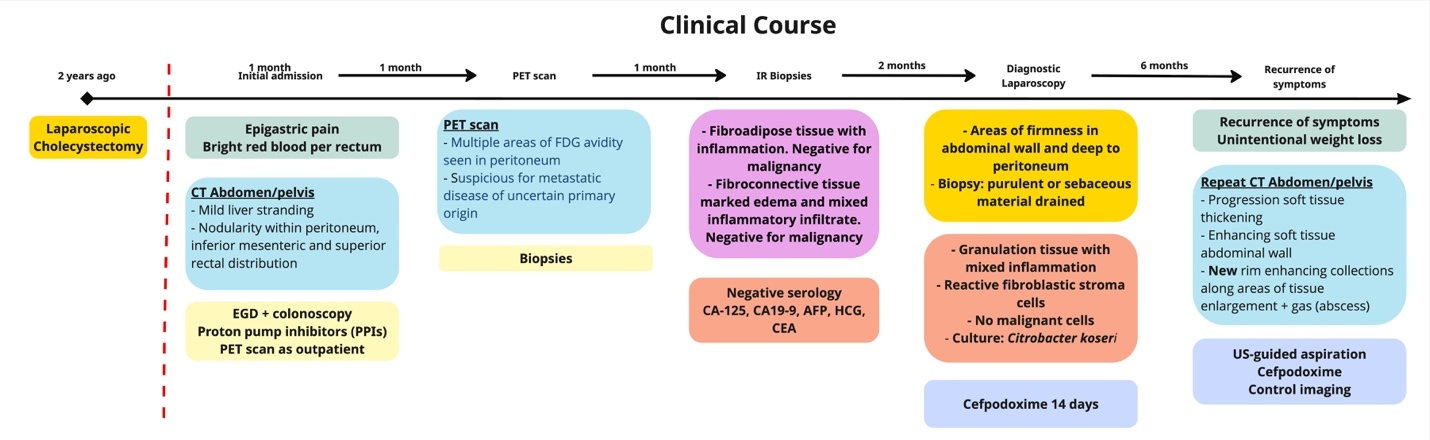

Patient is a 64-year-old man with a history of cervical spondylosis, lacunar stroke, hyperlipidemia, who two years prior underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy for severe acute cholecystitis during which gallstones were spilled in the peritoneal cavity. He presented to the emergency room with acute epigastric pain, bright red blood per rectum, nausea, and low-grade fever (38.5 Celsius degrees) (Figure 1). Physical examination revealed epigastric and right upper quadrant tenderness without peritoneal signs. Laboratory tests showed normal hemoglobin, white blood cells, platelets, and normal liver enzymes and lipase.

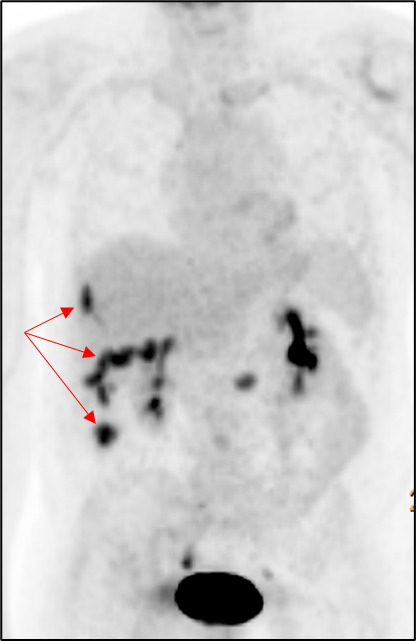

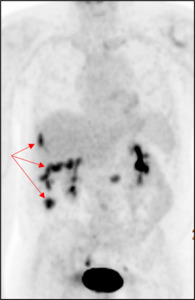

A computer tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis was performed and showed nodularity along the right hemidiaphragm, soft tissue nodularity within the peritoneum, nodular soft tissue along inferior mesenteric and superior rectal distribution, and indistinct areas of enhancement deep to right ventral abdominal wall concerning for peritoneal metastases (Figure 2). A positron emission tomography (PET) scan showed multifocal FDG-avid peritoneal lesions suspicious of metastatic disease of uncertain primary origin (Figure 3). Image-guided biopsies (CT- and ultrasound-guided) from the right upper and lower quadrants revealed only fibroinflammatory tissue, with negative microbiologic and cytologic results. Tumor markers (CA19-9, CA125, AFP, CEA, β-hCG) were within normal limits.

Given persistent pain and imaging findings, a diagnostic laparoscopy was performed, revealing dense adhesions of liver, greater omentum, and colon to anterior abdominal wall and areas of purulent material. Pathology demonstrated granulation tissue with mixed inflammation, no malignant cells, and cultures grew Citrobacter koseri. The patient completed 14 days of cefpodoxime with clinical improvement. Over the following months, he experienced unintentional weight loss and recurrent abdominal pain. Repeat CT scans showed progression of enhancing soft tissue lesions with rim-enhancing collections and foci of gas, consistent with abscess formation.

He was managed with prolonged suppressive antibiotics and local incision and drainage of superficial abscesses, again yielding C. koseri. Surgical resection was avoided due to extensive adhesions and risk of morbidity. The patient remains under follow-up with stable findings on serial imaging.

Discussion

Dropped gallstones (DGs) into the peritoneal cavity are a relatively common occurrence, and their incidence has increased with the widespread use of minimally invasive cholecystectomy techniques.1,2 Gallbladder perforation during cholecystectomy can result in the loss of stones into the peritoneal cavity in up to 30% of cases.3 Although most patients remain asymptomatic, up to 3% may later develop complications related to retained gallstones.4 The most frequent complications include abscess formation, inflammatory granuloma, and fistula development.2

Several intraoperative factors increase the risk of gallbladder perforation and stone spillage, including advanced age, male sex, acute or chronic inflammation, dense adhesions, friable gallbladder walls, poor visualization of the gallbladder fossa, limited working area, and excessive traction of the fundus or infundibulum.5 Meticulous surgical technique is therefore essential. Key maneuvers include maintaining gentle traction, using atraumatic graspers, careful dissection close to gallbladder wall, and aspirating bile when gallbladder is distended.5

If perforation and spillage occur, stones should be retrieved, and the gallbladder defect should be closed to prevent further leakage.6 Techniques to recover spilled stones include using graspers, suction, or endoscopic retrieval bags. To minimize additional spillage a gauze can be placed beneath the gallbladder, below Calot’s triangle. As the cholecystectomy continues, the stones are caught by the gauze.6

The pathogenesis of these complications is typically related to the gallstone acting as a foreign body, eliciting a chronic inflammatory response or serving as a nidus for infection.7 Clinically, DGs can remain silent for months or even years after surgery, as was observed in our patient who presented two years after cholecystectomy. When complications do arise, patients typically present with abdominal pain, fever, or localized swelling. In some cases, the presentation can be misleading, with imaging findings that mimic peritoneal carcinomatosis or soft tissue metastases, especially when multiple enhancing nodules or FDG-avid foci are detected.8

Radiologic differentiation is challenging. DGs located around the liver and in peritoneum may be mistaken for peritoneal metastatic implants or enlarged lymph nodes, as they often appear as round soft-tissue nodules with a high-attenuation peripheral rim on contrast-enhanced CT.2 Unenhanced CT can be helpful in revealing the calcified nature of these nodules, supporting the diagnosis of DGs.2 However, the presence of calcification is not entirely specific, as mucin-producing tumors may also contain areas of calcium deposition. Therefore, imaging must always be interpreted in the context of clinical history and prior surgical procedures.

Radiologically, these lesions often appear as heterogeneous soft-tissue masses or rim-enhancing collections that can be mistaken for malignancy.9 The presence of small, calcified foci within lesions may suggest gallstones; however, radiolucent stones can be missed, complicating diagnosis. PET scanning can further mislead clinicians by showing FDG uptake in inflammatory tissue, as occurred in this case, prompting extensive workup for cancer of unknown primary.

In our case, the initial CT and PET scan findings suggested peritoneal carcinomatosis or metastatic disease of unknown primary (CUP). This diagnostic dilemma is well-recognized, as CUP accounts for approximately 3-5% of all malignancies, with peritoneal involvement reported in around 13% of cases.10 The majority of CUPs represent adenocarcinomas, most commonly originating from the lung, pancreas, hepatobiliary system, or kidney.10 Because peritoneal metastases are a frequent manifestation of these malignancies, extensive oncologic evaluation is usually pursued, potentially delaying recognition of benign mimics such as DGs.

Histopathologic evaluation and microbiologic cultures are essential for establishing the correct diagnosis. In our case, multiple biopsies revealed chronic inflammation and fibroblastic reaction without evidence of malignancy, and Citrobacter koseri was isolated from peritoneal washings. C. koseri is a gram-negative, facultative anaerobic bacillus of the Enterobacteriaceae family, commonly found in the gastrointestinal tract and environment. While it rarely causes infection in immunocompetent adults, it has been reported in cases of abdominal abscesses and surgical wound infections, often associated with retained foreign material or necrotic tissue.11

Management of DGs related complications depends on the extent and accessibility of the lesions. Image-guided drainage and antibiotic therapy are the mainstays of treatment; however, definitive source control may require surgical retrieval of retained stones when feasible.12 In cases with multiple deep-seated or adherent collections, as in our patient, a conservative approach with prolonged or suppressive antibiotic therapy may be appropriate. Recurrence is possible if stones remain unretrieved, and long-term follow-up is recommended.

Conclusion

Most DGs remain asymptomatic, and complications are rare. However, a high index of suspicion is needed for a diagnosis of patients with persistent abdominal pain even years after cholecystectomy. DGs can serve as a chronic source of inflammation or infection, leading to radiologic findings that closely mimic peritoneal carcinomatosis or metastatic disease. Awareness of this potential complication can prevent unnecessary oncologic investigations and guide appropriate management

_and_coronal_(b)_ct_scan_images_showing_soft_tissue_prominence_along_ri.jpeg)

_and_coronal_(b)_ct_scan_images_showing_soft_tissue_prominence_along_ri.jpeg)