Introduction

Vaginal atresia is a rare congenital condition that usually manifests with primary amenorrhea.1 It occurs in approximately 1 in 5000-15.000 female births. Vaginal atresia is a development defect of the vaginal canal that takes place before the 20th week of gestation.2 It results due to an abnormal development of the urogenital sinus, which leads to a replacement of the caudal portion of the vagina by fibrous tissue.3 This hinders the natural outflow of uterine secretions. Vaginal atresia is therefore a risk factor for urinary tract infections and pyometra, which is an accumulation of pus in the uterus. Agenesis or atresia of the vagina can be observed as isolated developmental defect or as part of a syndrome complex with associated anatomical anomalies, such as Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome or Bardet-Biedl syndrome for example.4 Patients with MRKH syndrome present with renal anomalies in 30% of the cases. Vaginal atresia is also associated with skeletal anomalies, including fused vertebrae or anormal ribs and extremities. In our case, the patient presented with a bilateral vesicoureteral reflux, and the inspection of the outer genital showed a missing vaginal introitus. On evaluation, the anus was normally developed. Patient had no cardiac, intestinal, renal, or skeletal abnormalities. Endocrinological and genetic analyses were also unremarkable.

A classification established in 1998 by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine classifies the different anatomic types in müllerian anomalies or vaginal anomalies. Regarding this classification, vaginal atresia is considered as a type 1 anomaly: agenesis and hypoplasia of the uterus, cervix, and upper two-thirds of the vagina. Inside this classification, we can separate the vaginal atresia into three types: vaginal agenesis (observed in patient with MRKH syndrome), proximal vaginal atresia and distal vaginal atresia. Vaginal atresia can also be subclassified into transverse, longitudinal, or stenotic types. In this case, we present a patient with distal vaginal atresia.

Impaired drainage of uterine secretions, such as that caused by vaginal atresia, is believed to result in hydrometra, which can lead to urinary retention and subsequently pyelonephritis.4 The infection then spreads to the uterus and eventually causes pyometra. Although pyometra has been described in several cases in postmenopausal women, it remains extremely rare in children. To the best of our knowledge, neonatal pyometra has not been previously reported in the literature. We present the case of a newborn diagnosed with obstructive uropathy, dehydration, renal failure, pyelonephritis, and pyometra secondary to vaginal atresia. Additionally, we discuss the diagnostic challenges, clinical decision-making, and treatment complexities encountered throughout the patient’s care.

Case Summary

A 4-week-old mature newborn was admitted to our hospital with severe dehydration, hyperkalemia, hyponatremia, and acute kidney failure. Earlier in the day, the primary care pediatrician noticed a weight loss of 400g and decrease perioral intake. Since the 5th day of life, the patient experienced frequent stools and chronic diarrhea, prompting hospital admission.

Due to severe dehydration, the patient was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) and started on intravenous fluids. Meanwhile, a rapidly growing mass was observed in the lower mid-abdomen. An ultrasound scan showed a massive cystic mass in the abdomen with severe urinary obstruction. A subsequent CT scan revealed a markedly enlarged renal pelvis with reduced renal perfusion, bilateral megaureters, and a 9 x 5 cm cystic septated structure. (figure 1). The outer genital showed normally developed labia but no vaginal entrance. An exploratory laparotomy revealed an enlarged and protruding uterus. The ovaries and fallopian tubes were normally developed. Following uterine incision through the vagina, over 100 mL of purulent fluid was drained, and a Redon drain was placed. Immediately after drainage, urine began flowing through the inserted bladder catheter and intraoperative ultrasound showed a decrease in renal pelvic calyx dilatation. Uterine drainage analysis demonstrated a high cell count, mainly granulocytes. Uterine drainage grew Streptococcus anginosus, which led to the diagnosis of pyometra. In addition, urine culture grew Streptococcus anginosus and Escherichia coli.

After surgery, the uterus was flushed several times a day through the inserted drain and intravenous antibiotics were administered. After several days in the PICU, the patient was transferred to the pediatric surgical unit in stable condition. Fluoroscopy over the placed drain showed a long-segmented vaginal atresia. The drain was removed on the 10th postoperative day following the cessation of drainage output, and the child was subsequently discharged from the hospital.

During post-hospitalization check-up, ultrasound showed an increase of the intrauterine fluid accumulation and a urinary tract infection. After consulting with pediatric nephrology, a renal scintigraphy revealed a hemodynamic relevance due to the fluid accumulation. A percutaneous intrauterine drain was inserted with purulent drainage. A voiding urosonography demonstrated bilateral vesicoureteral reflux. Due to the repeated pyometra and recurrent urinary tract infection, an MRI was conducted to assist in planning the definitive surgery. The MRI showed a distal vaginal atresia with the presence of a septum and a normal developed cervix.

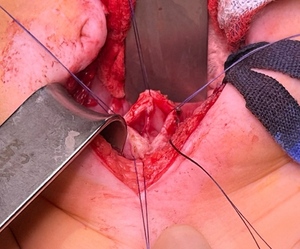

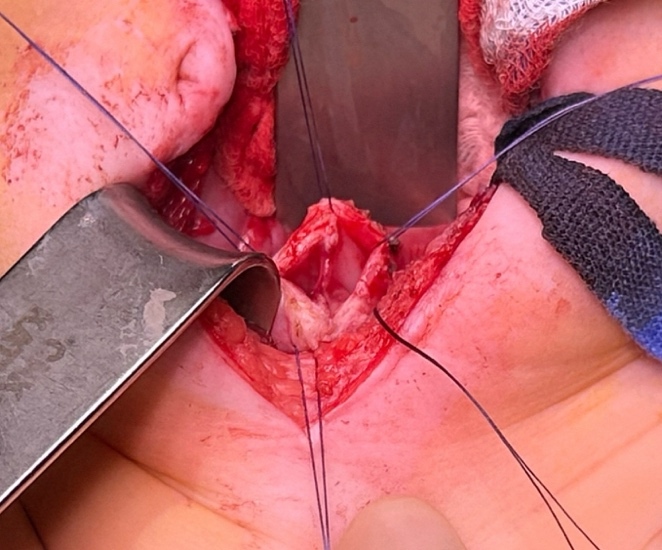

Once our patient reached 4 months old, the final surgery —a combined abdomino-perineal vaginal pull-through with septum resection— was performed by our department (figure 2). Following the procedure, a catheter was placed in the neovagina to prevent stenosis of the newly created vaginal canal and to ensure safe drainage of secretions. Antibiotic prophylaxis with cotrimoxazole was discontinued, and metronidazole along with cefotaxime was administered perioperatively. The catheter was removed after one week, with a follow-up scheduled to initiate regular neovaginal dilations. A new catheter was then reinserted and left in place for another week. Frequent follow-ups were performed with regular dilatation of the neovagina to avoid stenosis.

Conclusions

Pyometra is a serious condition that can be life-threatening, especially in newborns.5 Vaginal atresia can cause obstructive uropathy, pyometra, and in extreme cases, acute renal failure. In this case, a combination of vaginal atresia and pyometra caused renal congestion, pyelonephritis, reduced kidney perfusion, and acute renal failure in a neonate. In this case, timely exploratory laparotomy and uterine drainage were crucial, as resuscitative fluid therapy alone could have resulted in terminal renal failure. The observed increase in the size of the mass on imaging was likely due to fluid replacement during the treatment of dehydration. Pyometra can be treated with antibiotics and decompression of the uterus.6 Surgical reconstruction of vaginal atresia is complicated and must be tailored to each individual case. Further imaging, such as fluoroscopy and MRI, are necessary to characterize the length and type of vaginal atresia to prepare for surgery.3,7 Definitive surgical therapy for vaginal atresia can be planned once the infection is under control and the patient is old enough for reconstruction. In our case, an abdomino-perineal vaginal pull through surgery was performed. Perioperative insertion of a catheter and regular dilatations of the neovagina during follow-ups are necessary in the beginning to avoid stenosis of the neovagina.

The aim of surgery is to allow regular menstruation and sexual intercourse. In our case, we decided to perform an early reconstructive surgery at 4 months of age. This decision was made to prevent recurrent urinary tract infections and repeated pyometra as the patient already suffered multiple infections. Distal vaginal atresia combined with pyometra still remains extremely rare in newborn. A thorough physical examination, including assessment of the genital status, is essential to consider all differential diagnoses. The timing of reconstructive surgery should be tailored to each individual, with the possibility of early intervention carefully considered. Cases like these can help raise awareness of the condition, promoting earlier detection and treatment.

Acknowledgment

Thanks to Carolyn Fan, MD, Dallas, Texas, US for the linguistic proofreading.