Introduction

Epigastric hernias occur along the abdominal wall, between the xiphoid process and umbilicus, and in the midline, through a fascial defect in the linea alba.1 Epigastric hernias make up about 1.6%–3.6% of all abdominal hernias, and only 0.5%–5% of all operated abdominal hernias.1 They usually contain preperitoneal fat, but there have been case reports in the literature of epigastric hernias containing unusual content, like colon or stomach.1 We report an unusual case of a female patient in her 80s with an epigastric hernia containing her gallbladder.

Gallbladder herniations are rare, with only a small number of published case reports.2 Associated risk factors include female sex, advanced age, prior operation(s), and a prior history of hernias.3 Another important association with gallbladder hernias is carcinoma of the gallbladder.4,5 Types of gallbladder herniations that have been documented include internally (through the foramen of Winslow), parastomal, epigastric, incisional, and ventral.2,3 Of these, incisional hernias appear to be the most common, with herniation tending to occur through a prior right upper quadrant incision. To the best of our knowledge, an epigastric gallbladder hernia has only been reported in literature once.2,6

Case Summary

We report the case of an 81-year-old female who presented to our outpatient clinic for evaluation of an epigastric hernia containing a large portion of her gallbladder.

The patient had a past medical history of early-onset dementia, monoclonal gammopathy, arthritis, asthma, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. There was no history of prior abdominal surgery. History taking was somewhat limited due to her dementia and was supplemented by family accounts and the medical record. Patient first noticed the bulge on her upper abdomen several months prior to her presentation. The bulge was associated with intermittent pain, swelling, and firmness that would self-resolve. Patient had presented to an Urgent Care two months prior and was instructed to go to the Emergency Department for further evaluation but did not follow up. She did have an approximately 25-pound weight loss noted by her primary care physician soon after her visit to Urgent Care that prompted further workup with an outpatient CT scan.

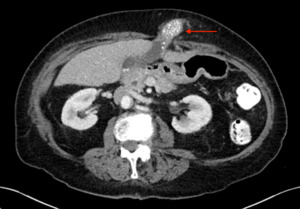

One month prior to her presentation to our outpatient clinic, the patient underwent a CT scan of her abdomen and pelvis with IV and oral contrast. This demonstrated the herniation of a large portion of the gallbladder fundus and body into an epigastric (supraumbilical ventral wall) hernia. The herniated portion contained numerous stones (Figure 1). There appeared to be some mild inflammatory fat changes versus hypervascularity in the abdominal wall surrounding the herniated gallbladder. There was no significant pericholecystic fluid, abscess, or bile duct dilatation. On physical examination, the hernia was found to be firm, non-reducible and moderately tender. Given its state of incarceration and associated symptoms, elective surgery to remove the gallbladder and repair the hernia defect was recommended, and she underwent a peri-operative risk assessment.

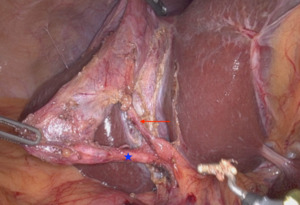

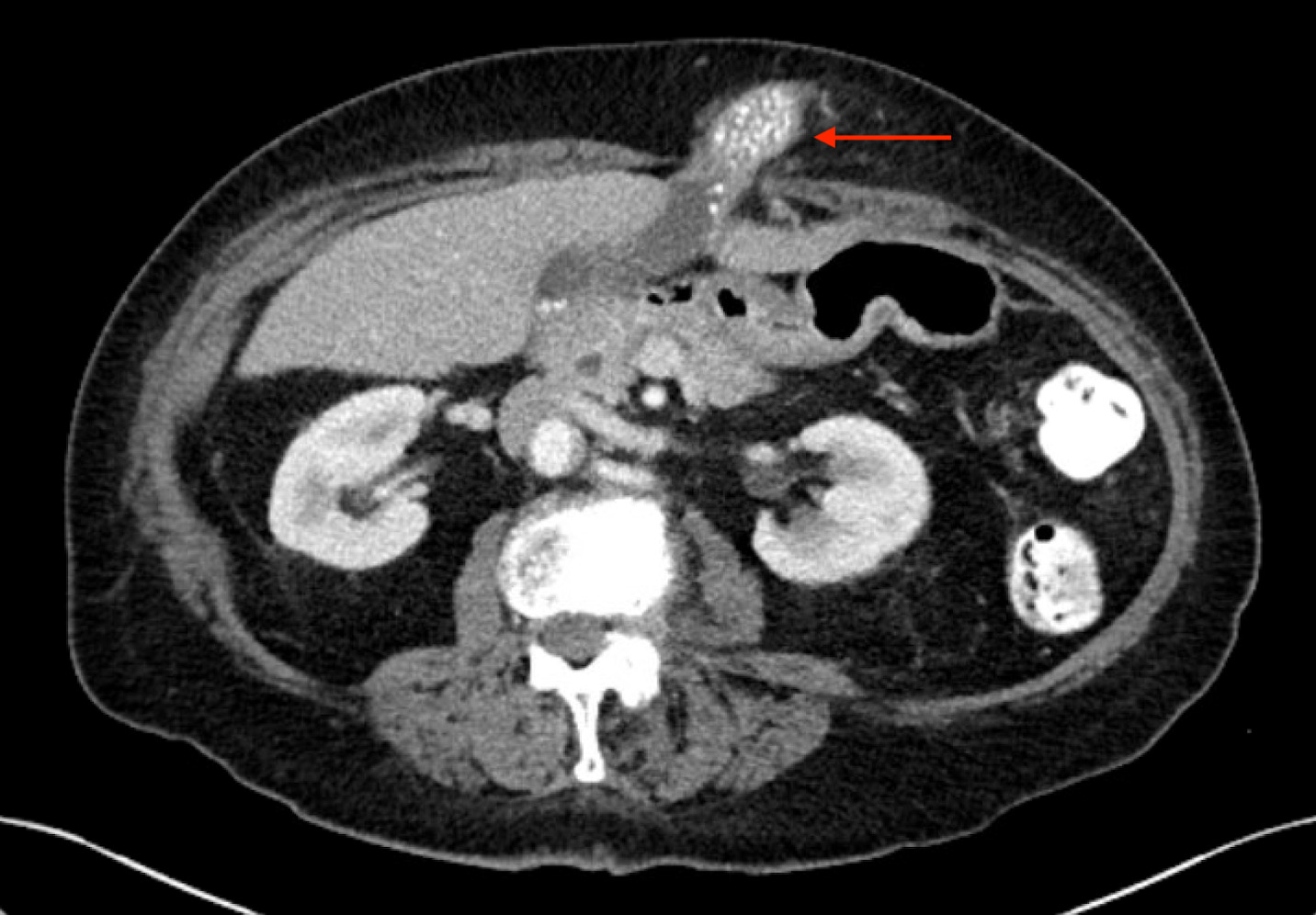

Three weeks later, the patient presented for a robotic-assisted laparoscopic cholecystectomy and epigastric hernia repair. Upon abdominal entry, numerous filmy adhesions were noted from the omentum to the upper anterior abdominal wall. Adhesiolysis was performed laparoscopically to allow for safe robotic port placement. The Da Vinci Xi robot was then docked. The gallbladder and adjacent omentum were found to be incarcerated within the epigastric hernia, and they were gently reduced laparoscopically (Figure 2). Cholecystectomy was then performed in standard fashion; critical view of safety was attained (Figure 3). The specimen was placed in a retrieval bag. The epigastric hernia sac was resected and was placed in a second retrieval bag. The robot was then undocked, and ports were removed. A vertical epigastric incision was made, and both retrieval bags were removed via the epigastric defect. Finally, the 2 x 2 cm hernia defect was repaired primarily with four interrupted figure-of-eight 0-Ethibond sutures. The patient recovered from surgery in the post-anesthesia care unit and was discharged the same day after surgery. She followed up in clinic three weeks later and reported resolution of her upper abdominal pain and improved appetite. The patient reported no associated complications.

Discussion

The pathophysiology of gallbladder herniation has been theorized to be attributable to gallbladder mesentery elongation as the patient ages coupled with anterior abdominal wall weakness or pre-existing hernia.2,3 Others have hypothesized that inflammatory changes of the gallbladder may contribute to a site of decreased local resistance within the abdominal wall musculature, at which the gallbladder mucosa herniates through.3,7 Given the numerous types of gallbladder-containing hernias, perhaps both mechanisms may contribute to the etiology of this unique presentation. In our patient the gallbladder appeared to have chronic inflammatory changes, both based on clinical history of recurrent pain episodes as well as intra-operative findings of adhesions to the surrounding tissue. However, it is unclear, between the hernia and the inflamed gallbladder, which is the “chicken”, and which is the “egg” in many patients, including our patient. Epigastric hernias do spontaneously occur along the linea alba, as in this patient, which is hypothesized to be an area of congenital and/or acquired abdominal wall weakness. Due to limitations in obtaining a history for this patient, it is not clear if our patient had previously had symptoms concerning for biliary colic or chronic cholecystitis.

Patients with a gallbladder hernia will commonly present with an irreducible and painful hernia, but vomiting and bowel symptoms will usually be absent.3 In the case of strangulation or incarceration, inflammatory and white cell count may be elevated.3 Acute cholecystitis may happen while the gallbladder is herniated, either because of a gallstone obstructing the cystic duct or because of the hernia ring causing obstruction of the cystic duct or cystic vasculature.6 Like other etiologies of cholecystitis, liver function tests will be normal or mildly abnormal. Generally, if a gallbladder herniation is suspected, an abdominal bulge seen on a patient should likely not be reduced (if anything more than minimal pressure over the hernia is required) because of the risk of rupture and peritonitis.2,5

A CT scan with IV and oral contrast is the imaging test of choice to diagnose ventral abdominal herniations.5 On CT scan, a gallbladder hernia can be suspected when the gallbladder is absent from its normal anatomical position and a walled structure is present within the hernia that does not contain oral contrast.2 The first step when looking at a ventral hernia on a CT scan is to try to rule out small bowel involvement. For this reason, oral contrast can be useful prior to obtaining the CT scan. Pijpers et al. advocated for MRCP to be used routinely after gallbladder herniation is suspected on a CT scan.7 They stated that this helps rule out gallbladder carcinoma and delineate the tissue planes between the gallbladder and abdominal wall for surgical planning. In our patient, the CT scan clearly demonstrated herniation of an otherwise relatively normal appearing gallbladder, and we felt that no further imaging was necessary as it would not have altered our management.

The definitive treatment of a herniated gallbladder is surgical, though the type of procedure depends on the individual patient and clinical scenario. In a recent systematic literature review by Samsami et al. in 2023, they found 65 cases of ventral abdominal wall gallbladder hernia. In older literature, an open midline laparotomy was recommended due to better exposure of the hernia sac and neck.2 However, as expected, Samsami et al. also found that more recent literature has recommended the laparoscopic approach for cholecystectomy and herniation repair in uncomplicated ventral gallbladder hernia, though they still recommended open laparotomy in the case of cholecystitis or perforated gallbladder.5 In our elderly patient with an uncomplicated presentation and clear imaging findings, a robotic-assisted laparoscopy was chosen. To date, this is the first case of a robotic-assisted gallbladder hernia reduction, and it demonstrates that this is a safe and effective option.

To our knowledge, the only case reported in the literature of an epigastric hernia containing the gallbladder is from 1985. In this case, the patient was over 90 years old and had an excessively long cystic duct and associated “floating gallbladder.”6 The epigastric hernia ring itself compressed the cystic duct and blood vessels, causing acute acalculous cholecystitis (no stones were found in this gallbladder).6 After reducing the gallbladder, they state that the mural changes of the gallbladder wall immediately improved.6 Instead of removing the gallbladder, they replaced it to its anatomical site and the hernia was repaired.6

Today, it is of unanimous opinion across the literature that cholecystectomy is indicated at the time of hernia reduction.2 Repair of the hernia defect is individualized. Most literature states the hernia defect should be repaired at the time of cholecystectomy.2,5 However, multiple reasons exist for why the hernia may not be repaired in the index operation. The primary reason for delaying hernia repair is likely due to concern regarding mesh use in a potentially contaminated field. This is most applicable when the hernia defect is large or not otherwise amenable to primary repair, and when acute cholecystitis or gallbladder perforation are present.5 For example, Backen et al. could not repair the hernia defect due to the damaged fascial edges not being amenable to primary repair and elected for postponed definite repair over utilizing mesh in the contaminated field or using biologic mesh.8 Similarly, parastomal gallbladder hernias are difficult to appropriately address given that mesh is typically needed for a robust repair and there is additional concern regarding maintaining blood supply to the stoma.2 Biologic mesh may be an option in a contaminated field, but the discussion of risks and benefits on the use of biologic mesh is beyond the scope of this case report. Most case reports of gallbladder hernias advocate for postponing definitive repair of the hernia defect when unable to repair the defect primarily in the case of acute infection.8 Our patient had a relatively small defect and viable fascia, and a primary suture repair without mesh was chosen. In summary, cholecystectomy is likely indicated for all gallbladder herniations, but the decision whether to repair the hernia defect at the time of surgery and how to perform this repair should be individualized to the patient.

Conclusions

Gallbladder herniations are rare, with only a small number of published cases. Most commonly, a gallbladder-containing hernia occurs at a prior incision site, usually in the right upper quadrant, but may occur in other locations such as parastomal, internally through the foramen of Winslow, or ventral/epigastric. Associated risk factors include female sex, older age, prior abdominal surgery/hernias, and gallbladder carcinoma. Aggressive attempts at reduction of gallbladder-containing hernias should be avoided due to risk of rupture, and mesh should be used cautiously in a potentially contaminated field.

_and_after_(2b)_reduction._(red_arrow_indicated_gallbl.png)

_and_after_(2b)_reduction._(red_arrow_indicated_gallbl.png)