Introduction

Managing large abdominal wall wounds in the presence of contamination from entero-cutaneous fistulae is very challenging.

We report a case of a successful treatment of such a complex wound through a close collaboration between surgeons and the wound and ostomy specialists.

Case Description

Patient is a 65-year-old male patient with multiple comorbidities that included obesity, coronary artery disease requiring bypass grafting, coronary artery stenosis treated with stenting, COPD, hepatitis C, polysubstance and alcohol abuse, smoking, and HTN.

In 2020, patient underwent an emergency exploratory laparotomy for intra-abdominal sepsis from a perforated sigmoid diverticulitis. A sigmoid colectomy, an end-colostomy, and a Hartmann pouch was performed. His post-operative course was complicated by dehiscence of his midline laparotomy wound on the second post-operative day, requiring a re-exploration of the abdomen and closure with external retention sutures.

Subsequently he developed a large ventral incision hernia and a large parastomal hernia.

Given concerns for high surgical risks due to patient’s extensive abdominal surgeries and his multiple comorbidities, repair of hernias and takedown of his colostomy were not recommended, and the patient was referred for the surgeries to our tertiary care center.

In July of 2023, patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy, extensive adhesiolysis, takedown of his end-colostomy from the left lower quadrant of the abdomen, a new colorectal anastomosis, and creation of a diverting loop ileostomy in the right lower quadrant of his abdomen. The 10 x 3 cm parastomal hernia was repaired with sutures. Repair of the large (30 x 10 cm) ventral incisional hernia required significant mobilization of the abdominal wall muscles and creation of large skin flaps bilaterally. Part of the right rectus muscle contained full-thickness ossification requiring debridement.

The midline abdominal wall closure was performed with sutures: two running looped, monofilament, non-absorbable sutures, internal retention sutures, and external retention sutures.

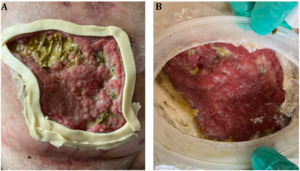

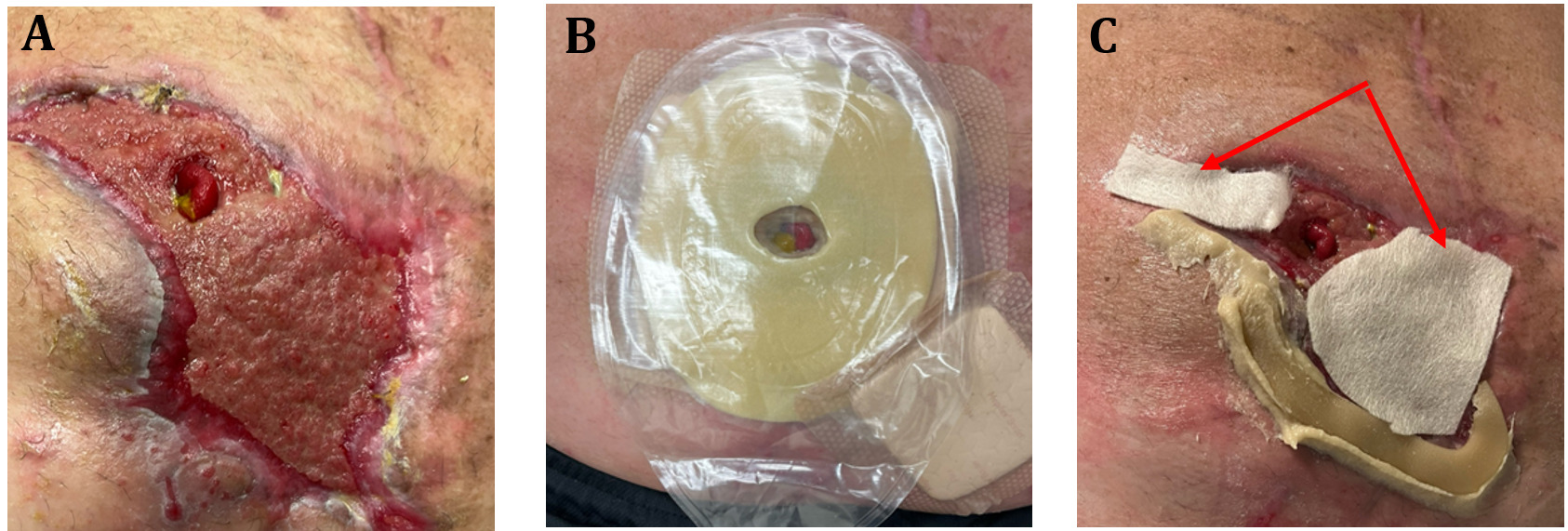

The immediate post-operative course was complicated by high ileostomy output (> 2 L/day) that persisted despite maximized fiber intake and anti-secretory and anti-motility agents. Furthermore, patient developed ischemia and necrosis of the abdominal wall skin to the right of the midline (Figure 1), due to the significant mobilization of the right abdominal wall muscles required for closure of the abdomen.

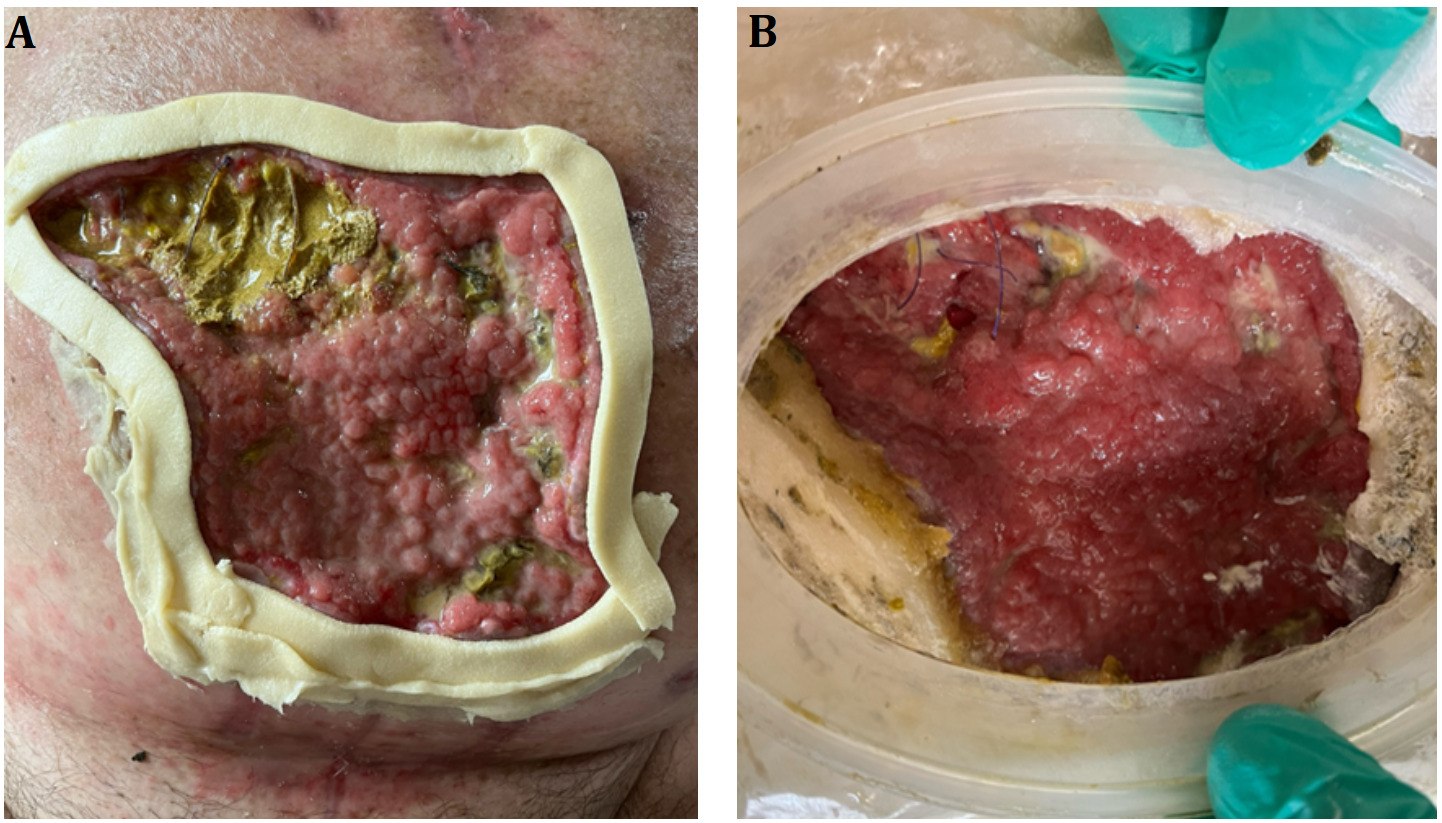

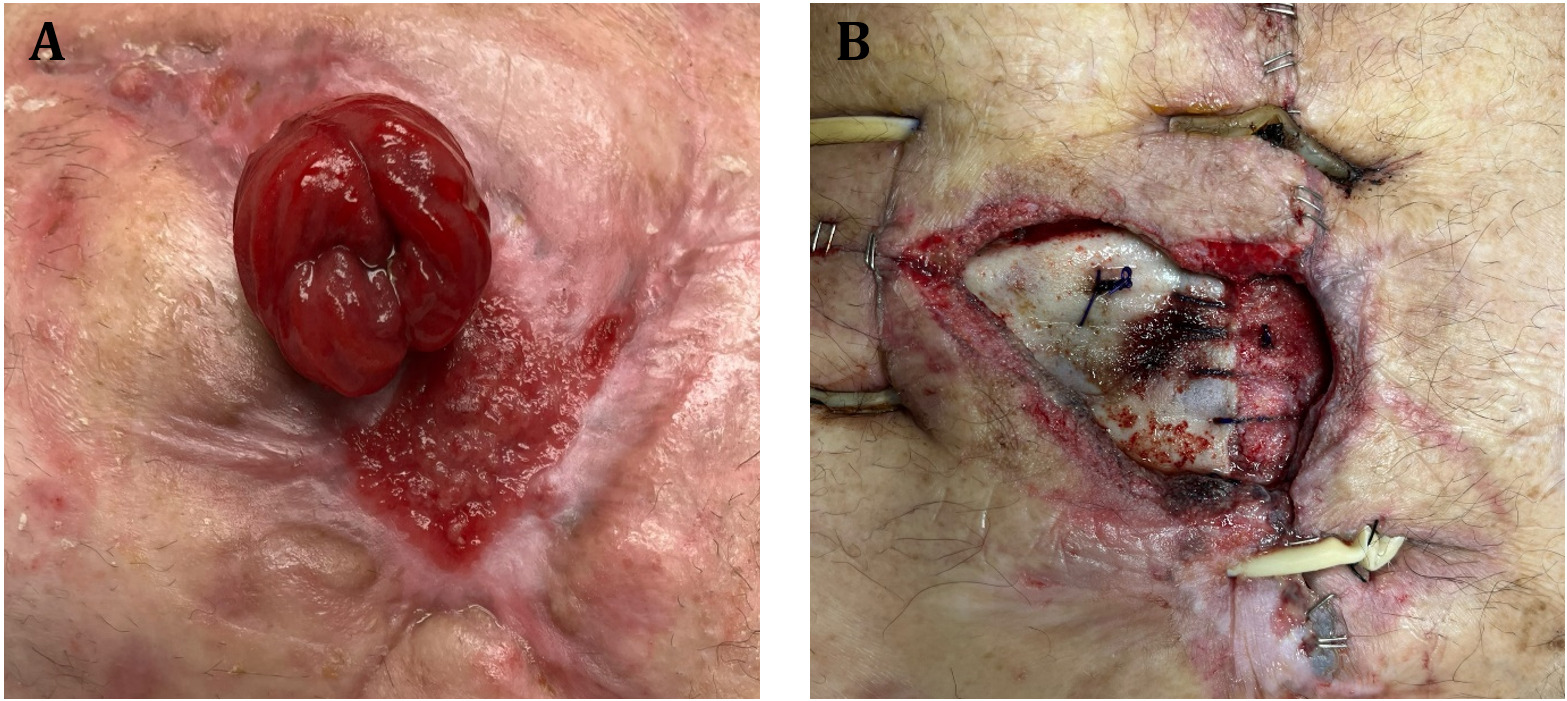

Given the refractory high ileostomy output, a shared decision was made to perform an early takedown of diverting loop ileostomy on post-operative day # 28. The surgery was performed via a horizontal incision in the right lower quadrant. The necrotic abdominal wall wound was debrided (Figure 2-A), and the wound was managed with negative pressure dressing therapy by our wound and ostomy specialists. Seven days after this surgery patient developed stool drainage at the site of the ileostomy takedown suggesting an entero-cutaneous fistula (Figure 2-B).

After weighing risks and benefits of an immediate surgical interventions, we concluded that delaying the surgery to allow maturation of the fistula would the safest option for the patient. This presented a unique and complex challenge: how to best care for an open abdominal wound around a productive entero-cutaneous fistula?

It is at this challenging moment that our very experienced wound and ostomy care specialists brainstormed innovative ways to manage the wound, with continued outpatient assessment and changes. These heroic wound care efforts are illustrated below in chronological order:

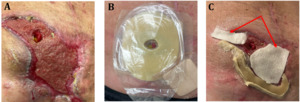

Stoma rings were applied around the entire wound bed and stoma paste was applied to the outside edge of the inferior aspect of the wound to ensure seal. (Figure 3-A). The wound was cleaned with hypochlorous acid, and petrolatum blend 3% bismuth tribromophenate was applied over the wound, prior to placement of a wound manager pouch (Figure 3-B). Patient was discharged to home with visiting nurse services and was instructed to empty the wound manager pouch whenever 1/4 full to assist with maintaining the seal. The fistula output averaged about 300 ml/day.

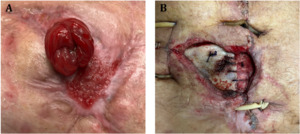

Four weeks later, the fistula site matured with a protruding stoma, and the wound had decreased in size with a good granulating base bed (Figure 4-A). As a result, the wound manager pouch switched to a smaller size (Figure 4-B). The wound was cover with border foam (silicone) in conjunction with stoma paste and convex rings. Due to the foam dressing not being able to handle wound drainage, calcium alginate (arrows) was introduced under foam dressing prior to application of the fistula pouch (Figure 4-C).

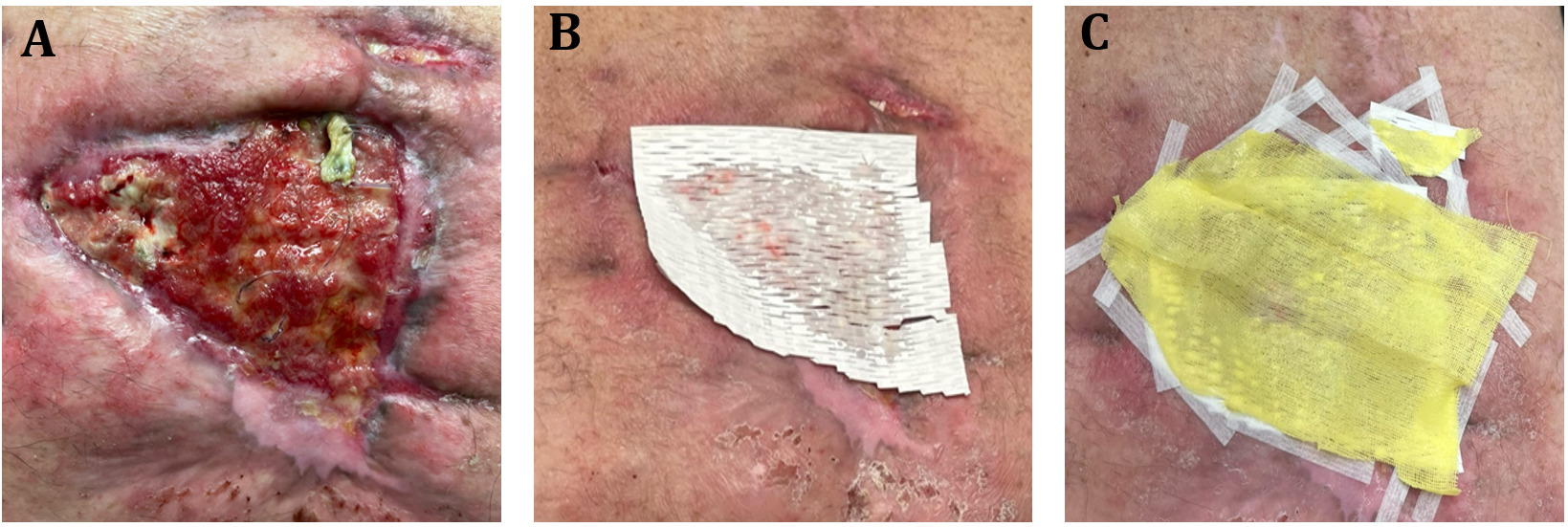

Four days later, a Fistula Crown® (McKesson, Irving, TX) was used to isolate the fistula from the surrounding abdominal wound and allow placement of black foam for negative pressure therapy over the peri-fistula wound (Figure 5-A). Stoma rings were placed under the base of the crown to protect the fragile wound base. After clear drape was placed over the sponge and Fistula Crown®, a hole was cut in the drape over the crown to expose its opening, and ostomy paste and powder was applied within the crown opening to ensure seal (Figure 5-B). A 2-piece pouching wafer was then applied around the crown (Figure 5-C), and a pouch was connected.

Over the next several months of outpatient therapy, the fistula matured into a stoma and the wound size significantly decreased (Figure 6-A). As such, in March of 2024, patient underwent a takedown of his entero-cutaneous fistula through a midline laparotomy. His right parastomal hernia was repaired with biologic mesh, the abdomen was closed with both internal and external retention sutures. Negative pressure therapy was placed over the abdominal wound. (Figure 6-B).

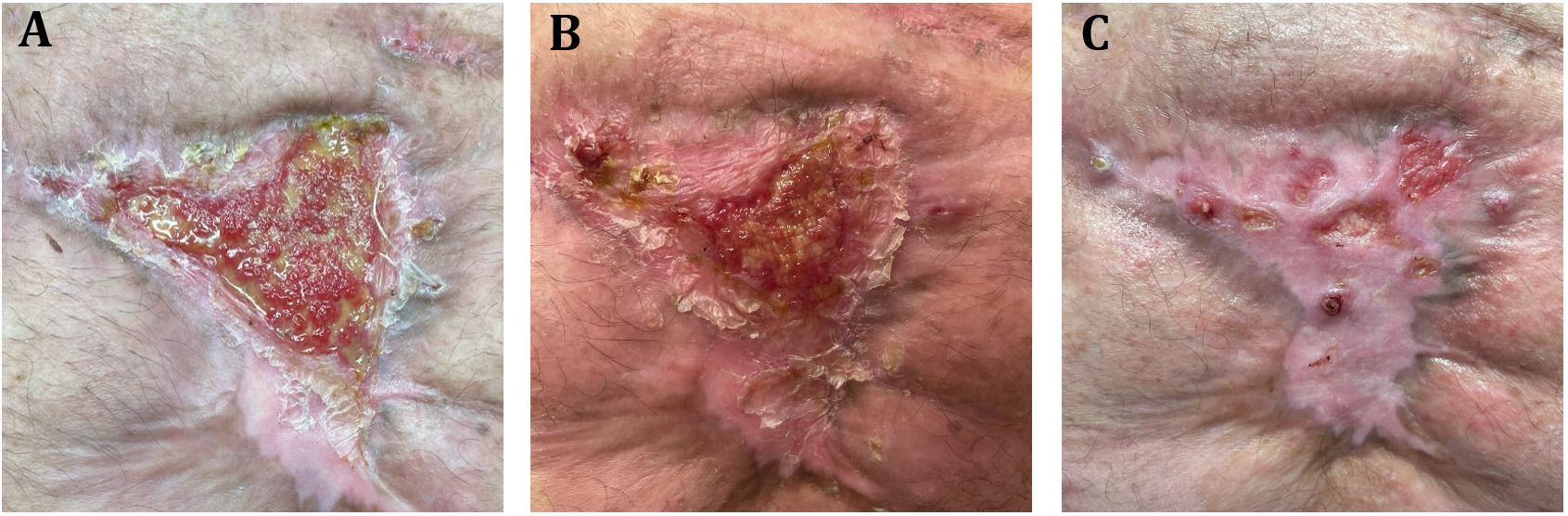

One month later, the wound showed significant granulation and its depth significantly decreased (Figure 7-A). At this point, we started to treat the wound with a synthetically constructed fiber matrix (Restrata®; Acera Surgical Inc., St Louis, MO)1 that resembles human extracellular matrix and supports ingrowth, retention, and differentiation. Furthermore, Restrata lowers the wound pH and creates an acidic environment with bactericidal properties. The matric fibers were placed over the wound bed (Figure 7-B) and Steri-Strips were used to stabilize the fibers, followed by Xeroform dressing (Figure 7-C). The wound was initially covered with moist gauze and border foam dressing. However, because it led to wound dermatitis, the bordered foam was discontinued, and abdominal pads were utilized to cover the wound.

Over the next several months of outpatient therapy, the wound size decreased until eventually the wound completely closed and epithelialized in August 2024. (Figures 8-A, 8-B, and 8-C).

Conclusions

The availability of experienced wound and ostomy care specialists and their close collaboration with the surgery team and outpatient nursing services are crucial for the successful management of complex abdominal wall wounds in the presence of entero-cutaneous fistulae.