Introduction

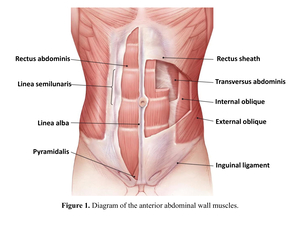

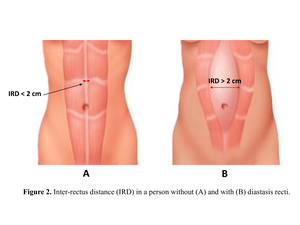

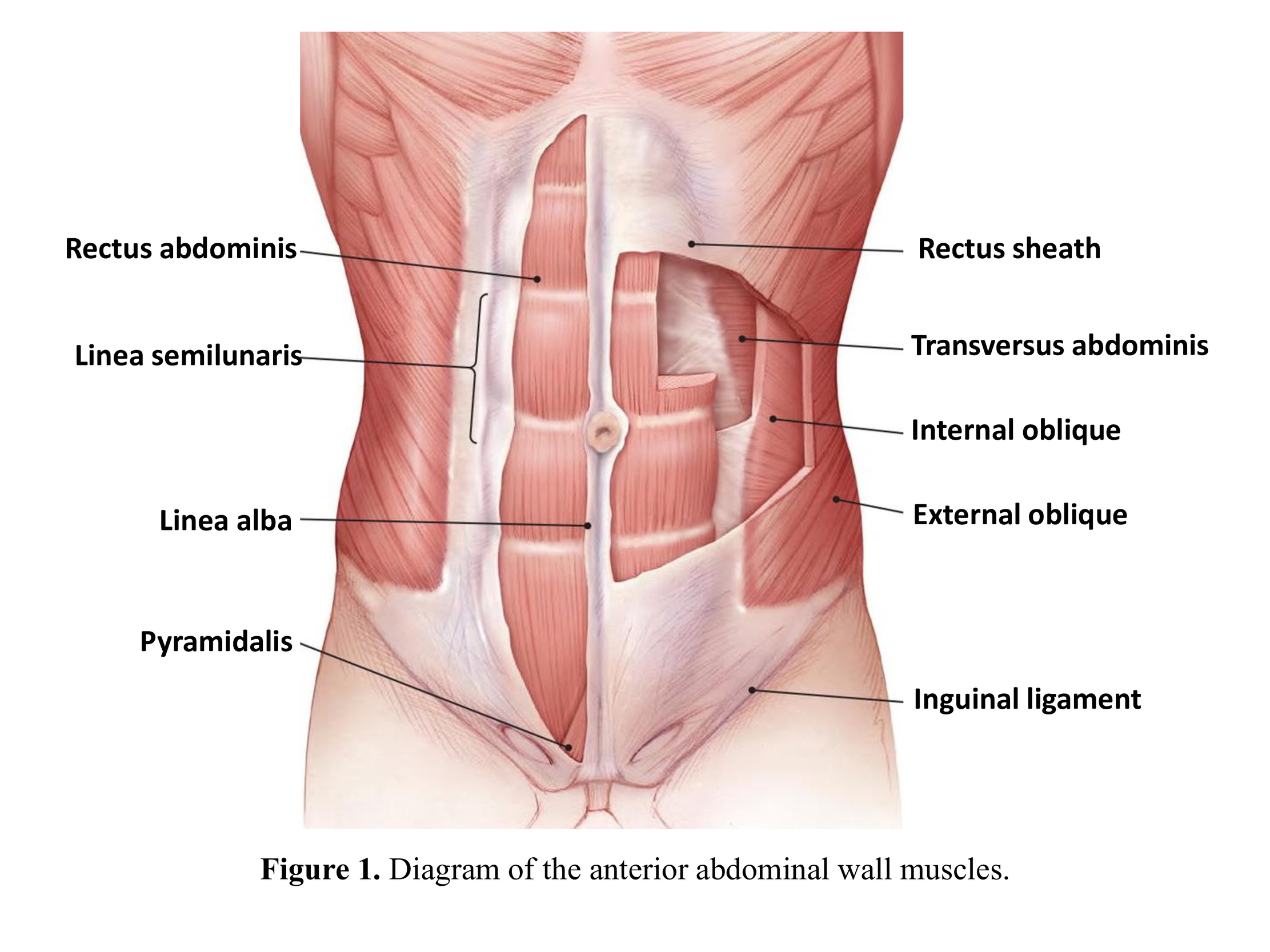

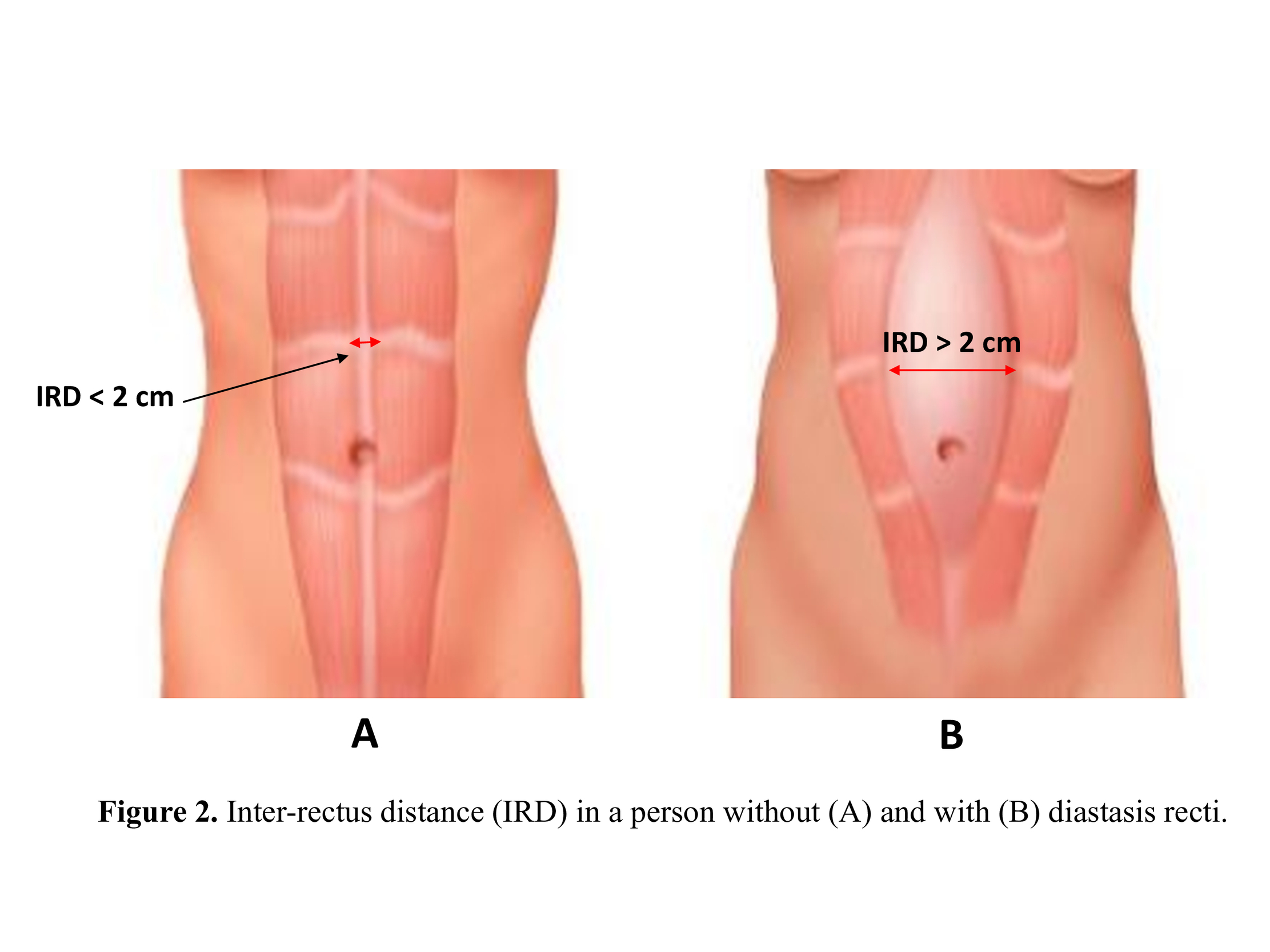

The muscles of the anterior abdominal wall are the rectus abdominis, external oblique, internal oblique, transversus abdominis, and pyramidalis (Figure 1). These muscles synergistically support movement and stability of the trunk, and respiration. These muscles are all supported by collagenous connective tissue labeled as fascia, which provides both anchor points for muscles to attach and structural support of the abdominal wall. One important fascial structure in the abdominal wall is the linea alba, which supports the rectus abdominis. The linea alba is attached to the xiphoid process of the sternum and runs vertically down the middle of the rectus abdominis muscles where it attaches to the superior pubic ligament. The rectus muscles are attached medially to the linea alba, and generally are separated by less than 2 cm. This distance is known as the inter-rectus distance (IRD) and is utilized to diagnose and categorize a condition known as diastasis recti. Diastasis recti occurs when the linea alba becomes stretched without a fascial defect, which can lead to a widening of the IRD and visible divarication of the rectus abdominis muscles (Figure 2). Diastasis recti can often be confused as a ventral hernia but differs because of the continuity of the midline with the absence of a hernia sac. Diastasis recti may cause physical and mental distress for the patient, which warrants the need for correction through conservative or surgical methods.1

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Diastasis recti has various causes, which depend on the medical and social history of the patient. In pregnant women a combination of the hormonal changes and increased intra-abdominal pressure from the growing fetus strains the connective tissue of the linea alba and widens the IRD. The changes in relaxin, progesterone, and estrogen levels during pregnancy leads to softening of connective tissue, which may play a part in the increased laxity of the linea alba in patients presenting with diastasis recti.2,3 In men, diastasis recti is associated with weight fluctuations, weightlifting, full sit-ups, congenital weakness in the abdominal muscles, and most often occurs in the fifth and sixth decade of life.1 Prolonged transverse stress on the abdominal wall combined with an altered collagen ratio of the fascia may also be contributing factors to the development of diastasis recti in men.4 Obesity and diabetes have also been explored as potential risk factors for developing diastasis recti. Obese individuals carrying more adipose tissue in the omentum and mesentery causes increased pressure on the abdominal wall, thereby increasing the strain on the abdominal connective tissue. A study by Grossi et al. displayed a decreased amount of collagen in the supraumbilical region of the linea alba of morbidly obese patients compared to non-obese cadavers of the same age group.5 Also, the physiological changes associated with diabetes (loss of muscle mass, function, and structure) may contribute to the weakening of the abdominal wall and resulting rectus divarication.1

Diastasis recti can present in newborns and infants due to reduced abdominal muscle activity or congenital abdominal muscle abnormality. This can, in turn, develop into a ventral hernia.1 Laxity and widening of the linea alba serve as risk factors for developing ventral hernias because of the resulting thinning of the connective tissue and weakening of the abdominal muscles. In a series of small umbilical and epigastric hernias, concomitant diastasis recti was identified in 45% of the patients. In this sample, patients with diastasis recti displayed a hernia recurrence rate of 31.2%.6 Overall, weakening of the abdominal wall musculature and connective tissue can lead to both diastasis recti and ventral hernia formation.

Epidemiology

Diastasis recti most commonly occur in post-partum women, with varying rates of occurrence depending on time post-partum. Sperstadt et al. identified 33.1% diastasis recti occurrence at gestation week 21, 60% at 6 weeks post-partum, 45.5% 6 months post-partum, and 32.6% 12 months post-partum.7 It tends to present more commonly supraumbilical because there are fewer transverse fibers in the supraumbilical linea alba compared to infraumbilical.2,4 A study conducted at a Brazilian maternity hospital by Rett et al. conducted identified supraumbilical diastasis recti in 68% of post-partum women with only 25% infraumbilical occurrence. They also identified a significantly higher infraumbilical IRD in multiparous women compared to primiparous women.8 Diastasis recti also most commonly presents supraumbilical in men as well. Wingerden et al. identified supraumbilical diastasis recti in 43% of a sample of 204 men presenting with chronic back and neck pain.9 These studies provide a general idea of the prevalence of diastasis recti but are limited in the demographics of their samples. Overall, larger and more diverse studies need to be done to provide a more comprehensive representation of the incidence of diastasis recti in the general population.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Patients may present with bulging along the linea alba when intrabdominal pressure increases. This can occur when exercising or straining the abdominal muscles and can result in aesthetic and functional complaints. It may be confused with a ventral hernia because of the appearance of a bulge upon physical exam.9,10 Although low significance, abdominal pain is positively associated with diastasis recti in recent post-partum women. Abdominal muscle function changes in diastasis recti may also be associated with pelvic floor dysfunction and stress urinary incontinence as well as lower back pain.11 Patients presenting with these symptoms may not know they have diastasis recti.12

Diastasis recti is most often diagnosed by measuring the distance between the rectus muscles. This can physically be done with abdominal palpations (finger width method), tape measures, or calipers. Sometimes, clinicians may use ultrasound to assess the linea alba and the IRD. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have also been reported for diagnosis in literature, but due to the high cost are not necessary for diagnosis of diastasis recti.12

Most studies identify diastasis recti as an inter-rectus distance of 2 cm or greater.13 However, there have been various proposed systems of classifying the severity and origin of diastasis recti. Most recently, the European Hernia Society classified diastasis recti by rectus muscle separation, concomitant hernia, and pregnancy or obesity status.14 Nahas et al. classifies diastasis recti based on myofascial deformity and etiology.15 This is grouped in patients with pregnancy, myo-aponeurotic laxity, congenital deformity, and obesity (Table 1).

Rath et al. classified diastasis recti based on IRD relative to umbilicus.16 The threshold values for diastasis recti according to this classification system change depending on if the patient is older or younger than 45 years old. Patients younger than 45 years are considered to have diastasis recti if their IRD exceeds 10 mm above the umbilicus, 27 mm at the umbilical ring, and 9 mm below the umbilicus. Patients older than 45 years meet the threshold at 15 mm above the umbilicus, 27 mm at the umbilical ring, and 14 mm below the umbilicus (Table 2).

The Beer et al. classification system is based on the IRD at the xiphoid and above and below the umbilicus.17 The threshold for “normal” is 15 mm at the xiphoid, 22m at a point 3 cm above the umbilicus, and 16 mm at a reference point 2 cm below the umbilicus (Table 3).

Different studies may utilize different classification systems, but most of them define diastasis recti as an IRD greater than 2 cm at certain points on the linea alba.13–17

Treatment

Understanding the risk factors can help patients reduce their risk of developing diastasis recti in the first place. Maintaining a healthy weight and physical exercises to strengthen the abdominal wall muscles are very important for diastasis recti prevention.

Once patients have developed diastasis recti, the associated aesthetic and functional distress often leads patients to explore methods of correction. Diastasis recti can be treated either conservatively through physical therapy or surgically with varying approaches. First-line treatment is generally physical therapy that includes an exercise program focused on strengthening the muscles of the abdominal wall. These exercises include pelvic tilts, pelvic floor training, and extremity strengthening with concurrent transversus abdominis contraction.18,19 Studies have shown that an abdominal muscle strengthening program concurrent with kinesio taping and electrostimulation therapy significantly decreases IRD in post-partum women.19 Conservative management of diastasis recti may not work for every patient, and other methods may need to be explored.20

Exercise resistant diastasis recti may need to be corrected surgically. Various studies exploring surgical repair of diastasis recti have displayed significant improvements in quality of life. Not only do patients experience cosmetic improvement, but also report functional improvement such as reduced back pain and urinary symptoms. Improvement in these symptoms are vital for sustained improvement in quality-of-life perception. In a 3-year follow up study of 60 post-partum patients that underwent surgical correction for diastasis recti there were no reported recurrences of diastasis recti or long-term post-operative complications. Surgical correction is a safe and effective method of correcting the divarication and can improve the quality of life for patients.21

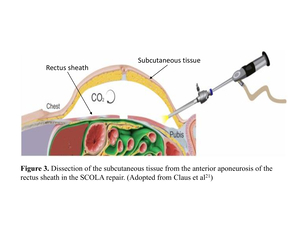

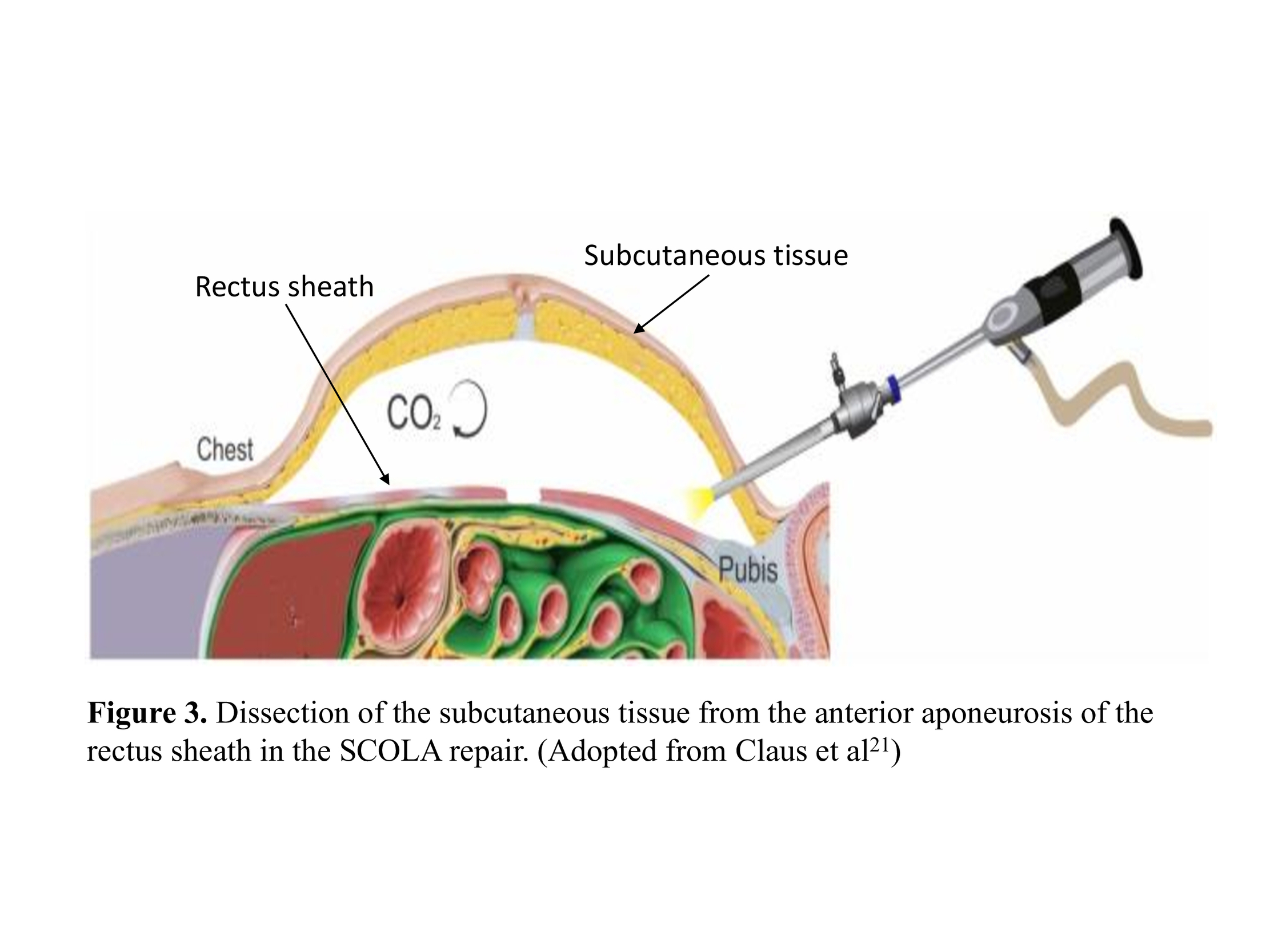

Laparoscopic abdominal wall repair is often used to repair ventral hernia concomitant with diastasis recti but have also been used to repair diastasis recti alone. Various studies analyzing laparoscopic have found it to have a high success rate, with most studies reporting almost a 0% recurrence rate 6 months after surgery. Most reported laparoscopic surgeries place the trocars suprapubic and periumbilical or suprapubic and in both iliac fossae.22 One approach described in the literature is the subcutaneous onlay laparoscopic approach (SCOLA). This involves creating a 2-cm incision just above the pubis and dissecting subcutaneous tissue until the anterior aponeurosis of the rectus abdominis is reached. Then, an 11-mm port is placed into the suprapubic incision for optic placement and two auxiliary 5-mm ports are placed laterally. Once the optic port is secured with a purse-string suture, the space created by dissecting the subcutaneous tissue from the anterior aponeurosis is insufflated with CO2 to provide easier maneuverability and visualization for the repair (Figure 3). This approach is often used to correct hernia defects in concurrence with diastasis recti. Placement of propylene mesh, along with plication, reinforces the abdominal wall and reduces the risk of recurrence22,23 Then, placement of a closed drain in the suprapubic incision helps reduce the severity of post-operative seroma.22 There have also been case reports describing robotic assisted laparoscopic surgery to repair diastase recti and a concomitant ventral hernia, which reported similar outcomes to traditional laparoscopic repair.24,25 Another case series describes a retro-muscular laparoscopic approach, where pneumoperitoneum is induced to provide a posterior view of the rectus muscles. This involves a modified version of the Rives-Stoppa hernia repair technique, where mesh is placed in a sublay position between the posterior rectus fascia and the rectus abdominis muscle. This approach provides clear visualization of the abdominal wall and provides opportunity to correct any hernia defects while also repairing the diastasis recti.26 Laparoscopic approach to diastasis recti repair may be beneficial for repair of concomitant ventral hernia and presents a less invasive approach to abdominal wall repair than open abdominoplasty.

Another approach that has been reported in the literature is with the guidance of an endoscope. This approach is similar to the laparoscopic approaches but involves placing the endoscope into a small periumbilical incision rather than through a suprapubic port.27 The periumbilical approach offers a hybrid approach between laparoscopic and open abdominoplasty. One key difference between laparoscopic approaches and endoscopic approaches is the violation of the anterior rectus fascia. In SCOLA, the anterior fascia of the rectus sheath is plicated and sutured to correct the widened linea alba. In certain endoscopic approaches, the plane between the anterior and posterior rectus fascia is entered by dissecting the anterior rectus sheath. Then, mesh is placed in a sublay position between the rectus muscle and the posterior rectus sheath before the anterior rectus fascia is sutured close.28,29 The mesh positioning in these approaches is like the sublay position seen in the modified Rives-Stoppa laparoscopic technique. However, the main difference is that the posterior rectus sheath does not get violated in the endoscopic approaches.26,29 The main benefit of endoscopic and laparoscopic approaches for diastasis recti repair is the minimally invasive nature of the operations, which lead to less scarring than traditional open approaches and minimal post-operative complications.27–30

There are contraindications that make minimally invasive methods too risky or difficult for diastasis recti repair. These include excess skin, subcutaneous fat, prior abdominoplasty, and obesity.28 The alternative to minimally invasive approaches is an open approach. Open diastasis recti repair is often performed along with an abdominoplasty; commonly known as a “tummy tuck” procedure. Abdominoplasties can be performed with concurrent liposuction or excess skin removal when necessary.23 A common approach to open abdominoplasties is through a transverse suprapubic incision lateral to the anterior iliac crests. During the abdominoplasty, when the subcutaneous tissue is dissected, the anterior rectus sheath can be visualized and incised. Then, the surgeon may decide to plicate the rectus fascia alone or lay a mesh with simultaneous plication.23 The recurrence rate for an open approach to diastasis recti repair is similar to the rate for laparoscopic and endoscopic approaches at nearly 0% at 6-month follow up.23 However, open approaches often result in larger scars due to larger incision sites compared to minimally invasive alternatives. In cases where patients are seeking improved cosmetic outcomes, the chance for larger scars and increased risk for the need of scar revision may turn them away from an open approach. However, patients with excess skin or subcutaneous adipose tissue may prefer an open approach that provides the surgeon the opportunity for simultaneous abdominoplasty and liposuction.10,23 The medical history and goals of the patient combined with the experience of the surgeon dictate the surgical approach of diastasis recti correction.

Regardless of the surgical approach, correction of diastasis recti can be performed with or without mesh. There have been various studies comparing the outcomes of suture-only correction and suture combined with mesh onlay. Mesh is utilized to reinforce the abdominal wall and is often placed in the retro-rectus plane affixed to the posterior rectus fascia. However, a satisfactory aesthetic outcome will not be achieved with mesh placement alone. The rectus fascia must be approximated to fix the visible divarication of the rectus muscles.10,31 The technique most frequently used to approximate the rectus fascia is through plication of the anterior rectus sheath utilizing continuous or interrupted sutures.32 Studies have compared non-absorbable and absorbable sutures in diastasis recti correction, which displayed no significant difference in the type of suture used for plication.13 Correction of diastasis recti can be done without concurrent mesh placement but may increase the risk of recurrence. A systematic review identified recurrence in 6 percent of suture-only patients and only 0.6 percent of mesh patients.33 Mesh is almost always used for patients with concomitant ventral hernias, but it can also benefit cosmetically as well. In a prospective study comparing mesh versus suture plication, the researchers identified a 0% complication rate in the mesh group and a 19% complication rate in the standard abdominoplasty group.34 Retro-rectus mesh provides mechanical support for the abdominal wall and provides a platform for the soft tissue to heal. Although, one of the complications that has been associated with mesh placement is chronic abdominal pain. In certain cases, the mesh can trigger a foreign-body inflammatory response and cause chronic pain. It is critical that the surgeon utilizes the appropriate type of mesh and places the mesh strategically to reduce abdominal wall trauma.33 Polypropylene is the most frequently utilized mesh material in correcting diastasis recti.22,33–35 Overall, plication of the rectus fascia combined with a retro-rectus mesh onlay is the most common approach to correcting rectus divarication.

Conclusions

Diastasis recti can be distressing for patients, and successful treatment can lead to significantly improved quality of life. Patients may present to the surgical clinic thinking that they have a ventral hernia, but instead have a lax linea alba. First line of treatment for diastasis recti will be physical therapy to attempt to strengthen the transverse abdominis and approximate the rectus muscles non-surgically. However, there are many cases where the diastasis recti is exercise resistant. In these cases, surgical treatment should be considered. Surgical correction has been proven to significantly improve the quality of life of patients by reducing back pain, pelvic floor dysfunction, stress urinary incontinence, and improving abdominal aesthetics. The impact of diastasis recti on a patient’s quality of life combined with the increased risk of ventral hernia make it vital to correct with conservative or surgical means.