Background

Odontogenic cutaneous fistulas (OCFs) are rare dermatologic manifestations of chronic dental pathology, defined by an epithelialized sinus tract that establishes an aberrant communication between the oral cavity and the cutaneous surface of the face or neck. These lesions most commonly arise as sequelae of untreated, longstanding periapical infections or necrotic pulp, wherein the purulent exudate follows the path of least resistance and eventually breaches the skin—typically in regions such as the chin, cheek, or submandibular area.1

Due to their atypical presentation and distance from the primary dental origin, OCFs are frequently misdiagnosed as dermatological conditions, including epidermoid cysts, furuncles, or basal cell carcinomas.2 Their intermittent drainage, which may or may not be accompanied by dental symptoms, contributes further to diagnostic challenges, often resulting in repeated courses of ineffective antibiotic therapy or surgical interventions that fail to address the underlying etiology.3

Clinically, patients may present with a solitary, erythematous, and sometimes crusted or ulcerated lesion, occasionally discharging pus. A high index of suspicion is essential, particularly in lesions that persist or recur despite conventional dermatologic treatment.

Radiographic imaging plays a pivotal role in diagnosis. Periapical and panoramic radiographs are useful initial modalities to localize the causative tooth and evaluate periapical pathology. However, in recurrent or diagnostically ambiguous cases, multidetector computed tomography fistulography

(MDCTF) offers superior anatomical resolution, enabling detailed visualization of the fistulous tract and its origin.4 While histopathologic examination is seldom required, it may be warranted to exclude malignancy in atypical or non-healing lesions.

Definitive management necessitates eradication of the dental source—typically via root canal therapy or tooth extraction—which usually results in spontaneous closure of the sinus tract without the need for surgical excision. Once the odontogenic infection is resolved, the prognosis is excellent, with minimal risk of recurrence.5

Case Report

A 25-year-old male was referred in 2025 from a surgical outpatient clinic to our private radiology center in Aden, Yemen, with a four-month history of a persistent, dimpled, crusted nodule in the right submandibular region, associated with intermittent purulent discharge and recurrent episodes of low-grade fever (Figure 1). Notably, the patient denied any dental symptoms, including pain or swelling.

Initial clinical evaluation suggested a superficial cutaneous infection, and the patient was empirically treated over several months with various systemic and topical antibiotics, which provided only transient improvement. The initial differential diagnosis included an epidermoid cyst, furuncle, and infected sebaceous gland.

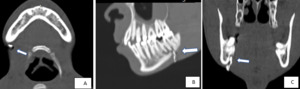

To further evaluate the condition, a multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) scan was performed using the following parameters: 110 kV, 120 mAs, 16 × 0.7 mm collimation, with image acquisition at a 3 mm slice thickness and secondary reconstruction at 1.5 mm. The patient then underwent an axial MDCT scan with post-processing multiplanar reconstructions in the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes.

The scan revealed a focal cutaneous opening without any evidence of a localized abscess or soft tissue mass (figure 2A). However, an osteolytic lesion was identified in the periapical region of the right mandibular second molar, accompanied by cortical thinning and a focal bony defect (Figure 2B, 2C).

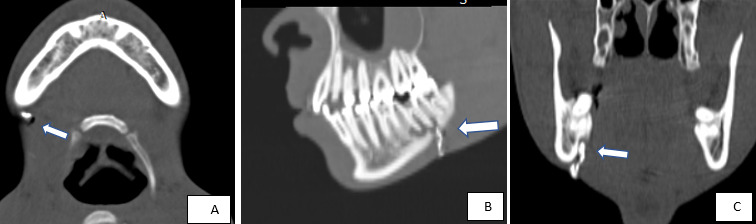

To further delineate the tract, CT-guided percutaneous fistulography was performed. A fine catheter was carefully introduced through the external skin opening, and approximately 1.5 cc of water-soluble iodinated contrast medium was slowly injected. The procedure demonstrated a well-defined, hyperdense, contrast-filled sinus tract measuring approximately 3 cm in length, extending from the cutaneous surface to a periapical abscess associated with the affected molar (Figure 3). These radiologic findings confirmed the diagnosis of an odontogenic cutaneous fistula

Discussion

An oral cutaneous fistula is a rare pathological conduit that facilitates drainage from the oral cavity to the skin surface, representing an atypical extraoral route for the spread of dental infection. In clinical and academic literature, the terms “fistula” and “sinus tract” are often used interchangeably to describe this phenomenon.6

Among oral cutaneous fistulas, those of odontogenic origin account for the vast majority of reported cases.7 These fistulas typically emerge as a consequence of neglected chronic dental infections—often secondary to carious lesions, traumatic injuries, or failed endodontic therapy—that result in periapical abscess formation. The ensuing inflammatory process leads to progressive resorption of the cortical bone and periosteum, with the infection following the path of least resistance into adjacent soft tissues, eventually creating a cutaneous opening.8,9

Guevara-Gutiérrez et al. conducted a pivotal epidemiological study analyzing 75 cases of odontogenic cutaneous fistula over an 11-year period. The average patient age was 45 years, with the highest incidence occurring in individuals aged 51 years and above (28%). The gender distribution showed a slight female predominance, with a female-to-male ratio of 1.14:1.8

Unlike acute odontogenic infections that present with pronounced pain and swelling, chronic dental infections often manifest without overt oral symptoms.10 Consequently, patients with odontogenic cutaneous fistulas may experience episodic drainage or remission, contributing to misdiagnosis and prolonged delays in definitive treatment11 In a retrospective study by Lee et al., 81.8% of patients were initially misdiagnosed, leading to inappropriate interventions such as antibiotic therapy, dermatologic procedures, or even surgical excision of the sinus tract.9

The clinical presentation of these fistulas can vary widely. Typically, they appear as small, erythematous, symmetrical smooth nodule, often measuring less than 2 cm in diameter, with or without purulent discharge.12 Other presentations include dimpling, sinus openings, cystic nodules, abscesses, scars, and ulcers.8Healing attempts may cause retraction of the overlying skin.12 The most commonly affected anatomical sites include the mandibular angle (36%), chin (28%), and cheeks (24%), with the lesion almost always appearing ipsilateral to the offending tooth.8

The differential diagnosis for a draining sinus of the face or neck must be comprehensive and include dental abscesses, congenital fistulas, salivary gland pathologies, osteomyelitis, epidermoid cysts, and malignancies such as basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma.9 Because the therapeutic strategies differ significantly, precise etiological identification is imperative.

Advanced imaging plays a central role in diagnosis. While panoramic radiographs and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) can provide valuable information on the dental source, MDCTF is considered the gold standard cross-sectional imaging technique for delineating complex or recurrent tracts.13 When combined with direct contrast injection into the cutaneous opening, MDCTF provides unparalleled visualization of the fistulous path and its relationship to surrounding anatomical structures.

As demonstrated in our case, iso-volumetric, high-resolution datasets obtained during contrast-enhanced CT scanning—combined with post-processed multiplanar reconstructions (axial, sagittal, and coronal) and advanced imaging techniques such as volume rendering (Figures 2–4) and maximum intensity projection—enable comprehensive mapping of the sinus tract. This approach allows for accurate identification of the tract’s type, length, internal origin, and any associated complications, such as bone erosion or abscess formation.14,15

Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is less commonly employed due to patient discomfort and scan duration, it offers superior soft tissue contrast and avoids ionizing radiation. Recent studies have shown MRI to be both feasible and diagnostically valuable in mapping odontogenic infections and their extraoral extensions, particularly when CT is contraindicated.13 In practice, MDCTF remains the most accessible and detailed cross-sectional modality for evaluating odontogenic fistulas.

Conclusion

This report highlights the intricate diagnostic challenge posed by odontogenic cutaneous sinus tracts, which often masquerade as benign dermatologic lesions and remain unrecognized until advanced imaging is employed. The high rate of initial misdiagnosis—reported in up to 50% of cases—reflects a critical gap in interdisciplinary awareness, particularly among dermatologists and surgeons unfamiliar with the subtle presentations of dental-origin pathologies.

Multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) and MRI have redefined the diagnostic paradigm, offering high-resolution, cross section multiplanar visualization that enables precise mapping of the fistulous pathway, delineation of the underlying dental source, and assessment of adjacent structural involvement. These imaging modalities not only avert misdirected treatments and invasive dermatologic procedures but also empower clinicians to pursue definitive, etiology-driven interventions. Broadening clinical vigilance and integrating radiologic precision are therefore essential in optimizing outcomes for patients presenting with enigmatic orofacial cutaneous lesions.

Ethics Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the use of clinical data and imaging in publication, with assurance of confidentiality and adherence to ethical standards.

_volume-rendered_ct_fistulography_images_showing_the_sinus_tract_from_the_dental_roo.png)

_volume-rendered_ct_fistulography_images_showing_the_sinus_tract_from_the_dental_roo.png)